Communities have the upper hand when it comes to protection. Community members understand the local context and have the necessary resources and connections to organize self-protection activities better than international aid organizations. For example, local communities have relationships with armed groups that international actors cannot simply replicate. Moreover, international organizations are often constrained by security risks or their inability to access remote areas in ways that locals are not.

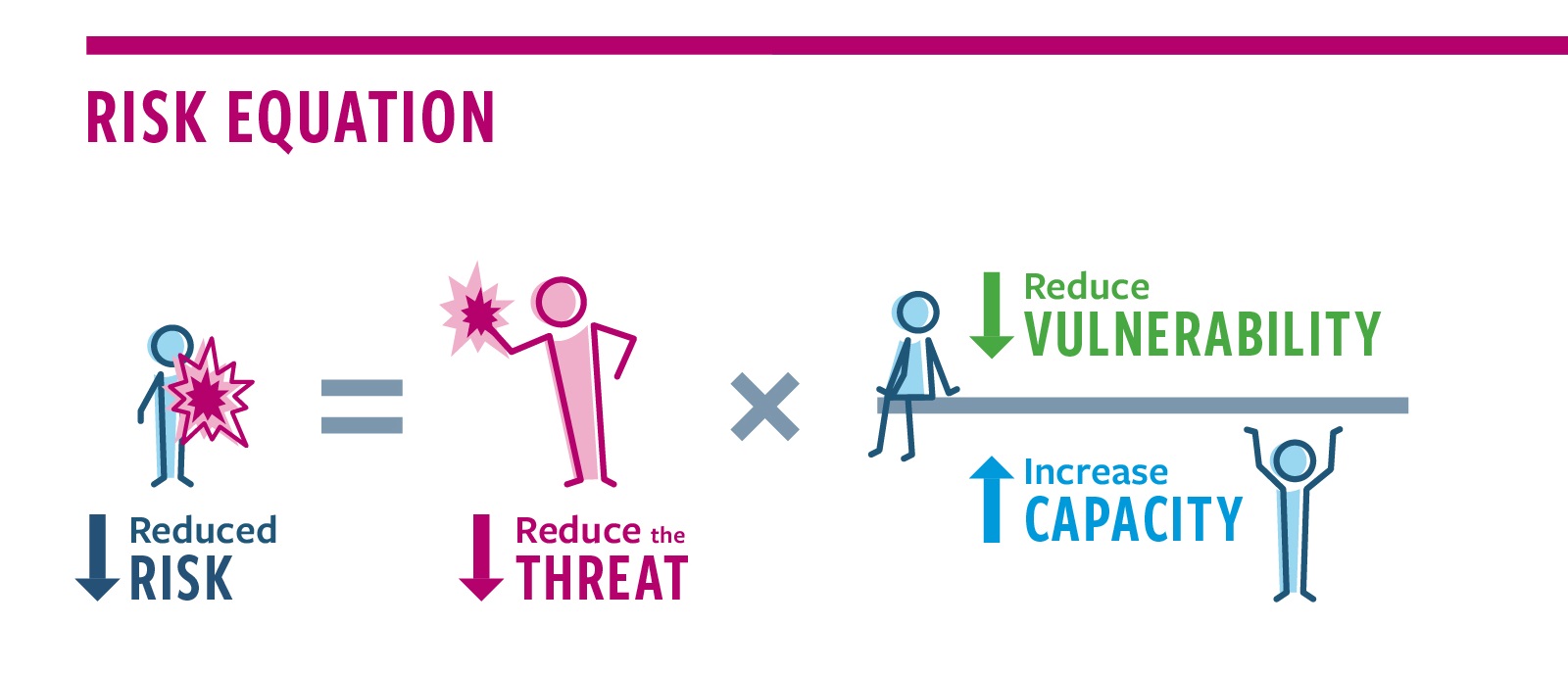

One starting point for enhancing the humanitarian community’s understanding of self-protection is Results-Based Protection (RBP). RBP is an approach to protection work that aims to better achieve protection outcomes, i.e. the reduced risk of violence, coercion, and/or deliberate deprivation. RBP also emphasizes that protection starts from the perspective of the affected community; any humanitarian work must build upon the strategies of the population themselves, as they will have the most information about the threats and risks, they face.

Self-protection strategies—actions that people take to protect themselves and reduce vulnerability and risk—are the leading means of protection for communities. Humanitarians have come to recognize the importance of identifying and building on community’s self-protection strategies, yet we sometimes overlook community self-protection in our protection programs. Some organizations excel at building on self-protection strategies, but this is not yet universal. In order to improve protection outcomes, the humanitarian community must develop a detailed understanding of self-protection and how its protection programs can support these strategies first and foremost.

Betcy Jose and Peace Medie, drawing on their work in Botswana and Ghana, developed a typology of self-protection strategies in their article “Understanding Why and How Civilians Resort to Self-Protection in Armed Conflict.” They write that there are three types of self-protection: non-engagement, in which civilians don’t interact with armed actors or international protection actors; nonviolent engagement, in which civilians interact with armed actors using peaceful means; and violent engagement, in which civilians or actors seeking to protect civilians use violent means—including joining or supporting armed actors—to reduce risk.

In a panel at the United States Institute of Peace, Oliver Kaplan explained another way of thinking about self-protection, which puts activities on a scale from less contentious to more contentious. Community self-protection activities can range from dispute resolution and the establishment of early warning systems to restrictions on weapons and protests against armed actors, among countless others. The latter strategies are more contentious; while these impose heavier costs on both state and non-state armed groups, they can also increase the risk of retaliation. While less contentious strategies are less costly for armed groups, these can still successfully reduce support for armed groups or help residents avoid violence.

Local populations can also use community organizations for self-protection. Formal peace organizations and informal organizations used for protection purposes, like religious organizations or village councils, both play a role. These organizations help people to form and implement protection strategies and build resilience, as well as to respond to protection risks outside of armed conflict.

For example, in Colombia, a community organization called the Association of Peasant Workers of the Carare (ATCC) negotiated with both state and non-state armed groups to conduct their own investigations of civilians who were accused of collaborating with “the enemy.” The ATCC successfully reduced violence against civilians as a result.

The humanitarian community is best suited to support nonviolent engagement strategies. The humanitarian community has acknowledged the importance of supporting self-protection strategies. The ICRC “Enhancing Protection” and ALNAP protection guide call on humanitarian agencies to support community protection strategies. However, the 2015 NRC Review of Protection report commented that self-protection measures were still not widely understood or analyzed by humanitarian actors.

Self-protection strategies may not necessarily successfully reduce risk, or they may create unintended risks for others. Contentious strategies may actually increase the risk of violence from armed actors, and cooperation with armed groups may unintentionally invite further abuses. External factors also play a part in determining how a community protects itself and the level of success its protection activities can achieve. For instance, research in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has shown that communities in which civilians and armed actors live in close proximity are more likely to cooperate with armed groups than to forcefully resist or protest them.

Thus, the first step for international protection actors must be to conduct a thorough analysis of the self-protection strategies of the target population. The first key element of RBP—continuous, context-specific protection analysis—guides humanitarians to identify the risk patterns that exist within a given community and the self-protection strategies (or capacities) a community has in place. Thereafter, humanitarians must continue to analyze and contextualize risk, revising and adapting their programs according to changing contexts and lessons learned.

Currently, despite the progress many organizations have made in identifying and supporting community self-protection strategies, the humanitarian community’s predominant conception of protection obscures a community’s role in its protection. Humanitarians perceive protection as an activity done to an affected population by a state or non-state traditional protection actor; this overlooks that protection is, primarily, the goal or objective that is carried out by affected populations. Humanitarians should look to RBP and its key elements to design their programs, for such programs are “likely to be more effective and durable.”