Humanitarians know that coordinated humanitarian response is like an enormous jigsaw puzzle – or, when resources are scarce, a high-risk game of Jenga. Ensuring that the right actors, sectors, and context-appropriate strategies are working in concert with one another to save lives, and alleviate human suffering on a massive scale, takes extraordinary effort. The enormity of this enterprise can mean that we sometimes lose sight of whether our actions and approaches are genuinely relevant and impactful in the lives of those we seek to assist. Whether we are helping to make people safer from the ongoing threats of violence, coercion and deliberate deprivation is of particular concern in humanitarian crises.

A range of studies and reviews over the years have highlighted systemic weakness and failures to address the pervasive risks faced by civilians in situations of armed conflict. For example, the 2012 “Internal Review Panel Report” on the UN’s response to the crisis in Sri Lanka and the Global Protection Cluster (GPC)-commissioned “Study on Protection Funding in Complex Humanitarian Emergencies” (2013) found inadequate contextual analysis, little investment in local capacities, lack of strategic orientation towards protection outcomes, and poor complementarity among various actors responding to the crisis. The “Independent Whole of System Review of Protection in the Context of Humanitarian Action” (2015) also noted a persistent “lack of strategic vision and contextual intelligence around protection matters.”

Frontline humanitarians will eloquently describe this problem to you: their responsibilities entail providing assistance and services – food or water or access to post-violence medical care – in accordance with a logframe. Yet when affected people tell them they need safety and an end to persistent assaults, abuses and mistreatment by a multitude of state and non-state actors, humanitarian staff are all too often not in a position to do more than listen.

Understanding the threats that people face in the midst of armed conflict, and who is vulnerable to specific threats and why, illuminates in sharp terms what our relevance to distressed populations should be about: practical and adaptable problem-solving rather than standardised and predictable humanitarian response. This is where three missing pieces of protection in the humanitarian puzzle can be found.

1. ACTIONABLE INFORMATION ANALYSIS

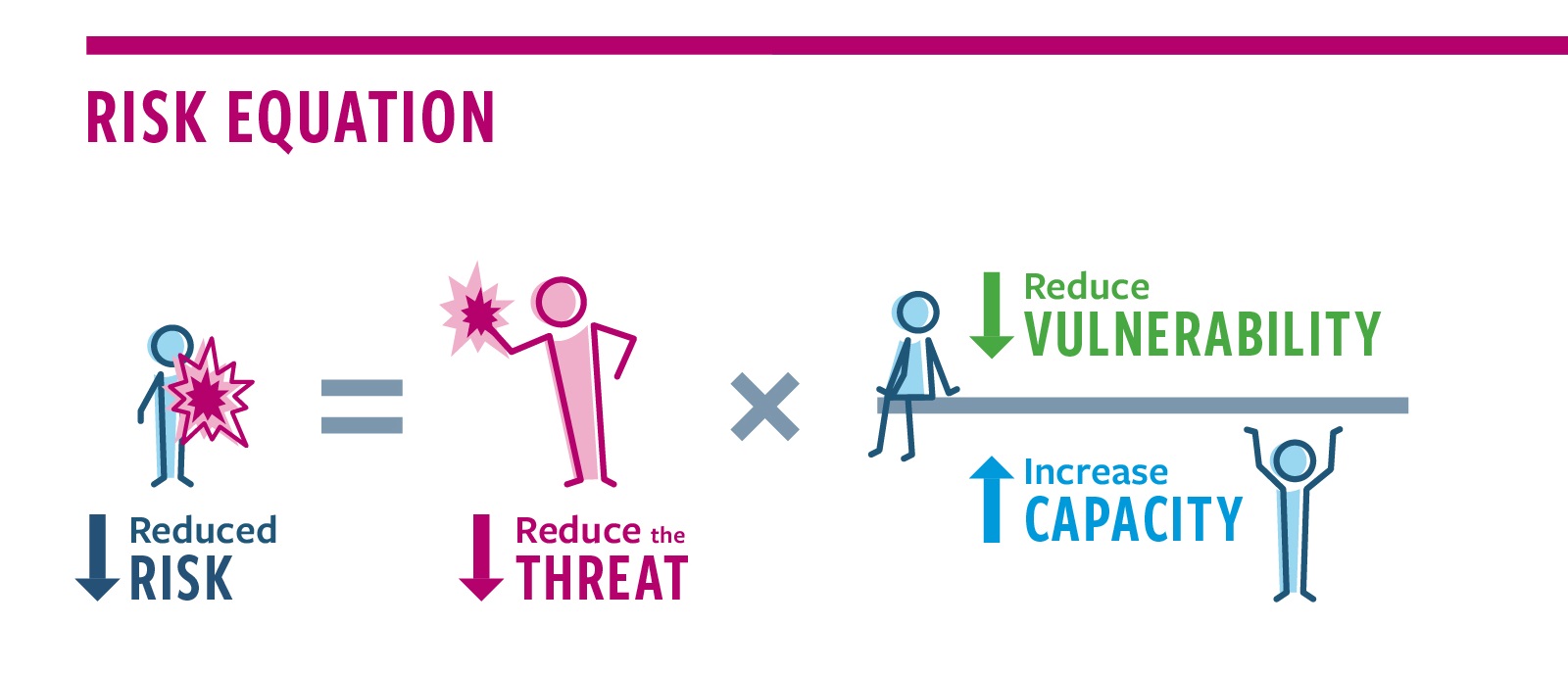

In numerous humanitarian crises actionable information and analysis does not reach those who can and should take action on the persistent pattern of threats that people face. Affected people and frontline humanitarian staff typically have detailed and nuanced understanding of the history and trajectory of an armed conflict, the roles of various actors, and the threats of violence, coercion and deliverable deprivation that people are exposed to. Too often, however, this deep base of knowledge is untapped and undocumented. There is a persistent lack of investment in collecting and analysing information about ongoing risk patterns. Such information and analysis would allow humanitarian actors to target specific threats and vulnerabilities, while working to enhance relevant capacities, to reduce these risks.

In reality, protection analysis too often focuses on vulnerability and neglects to unpack the behaviours, attitudes, motivations and policies of actors which are the source of the threats. Protection monitoring typically tracks the occurrence of incidents but does not capture sufficiently disaggregated information to identify what action should be taken to reduce threats or reduce vulnerabilities to the threats. When more detailed information collection is undertaken – for example, through focus groups, perception surveys and tracking threats — it is unfortunately not sustained. In fact, by breaking down the risk factors, we can create a baseline that can be continuously monitored (including through two-way communication with affected people) to see whether specific risks are increasing or decreasing. Such information would be invaluable to inform strategic decision-making by Country Directors, Humanitarian Coordinators, Humanitarian Country Teams and other actors. Good protection analysis allows us to identify options for concrete action that would not otherwise be apparent.

2. OUTCOM MINDSET

Secondly, critical to recognising and acting on a detailed understanding of protection risks is an outcome mindset. When we understand that protection is an outcome to be achieved – rather than an activity or a thing to be delivered – we can mobilise resources and effort across a range of actors, sectors and disciplines needed to reduce the risk people are experiencing. The starting point should always be to support actions that can be taken by communities themselves as far as safely possible. Affected people often understand their threat environment very well and have practical proposals that would help minimise their risk. In addition, research shows that communities with high internal cohesion and organisation can be very effective in directly negotiating with armed actors about how they should be treated. Indeed, many NGOs – such as Nonviolent Peaceforce, Geneva Call, and CIVIC — have effectively demonstrated that brokering conversations between affected people and military actors can result in behavior change by these actors and reduced risk.

Beyond a community’s own capacity to act, when we have the desired outcome of reduced risk clearly in mind, the importance of multi-disciplinary strategies becomes apparent. For example, if food insecurity is a critical factor driving women and girl’s exposure to sexual assaults, then food security programming must be a critical component to reduce women and girl’s exposure to that threat. However, food security interventions may not be sufficient to comprehensively reduce risk in most scenarios. For example, minimising the threat may additionally entail ensuring that military forces adopt disciplinary measures for misconduct on this front. This means that humanitarian response must be staffed by individuals able to engage with armed actors to bring about changes in their behaviour. Encouraging diplomatic engagement by other states may further support the necessary changes in military conduct. In this scenario, actions taken at multiple levels – all focused on reducing the risk of gender-based violence experienced by women and girls – may be critical to achieving the desired outcome.

An outcome mindset therefore enables us to see the pathways and combinations of actions necessary to reduce a particular risk, including strategies which expand a scope of influence beyond our own capacities and mandates. Furthermore, when supported by continuous protection analysis, changes in specific risk factors can be tracked and monitored to know whether the range of interventions undertaken are yielding the desired results. This gives us a basis to iteratively adapt our strategy to achieve the desired outcome. As noted by one participant in the Stocktake on the IASC Protection Policy and Centrality of Protection, “Protection outcomes take longer and require forward thinking and adaptive approaches to implementation which necessitates a change in mindset compared to how we operate today.”

3. AN ORGANISATIONAL LEARNING CULTURE

Continuous analysis and an outcome mindset underpin a capacity for iteration and adaptability. This leads us to the final missing piece: an organisational learning culture. Unfortunately, as highlighted in the Independent Whole of System Review of Protection in Humanitarian Action, there have been very few outcome-level evaluations on protection interventions and this contributes to a relative “learning deficit” about protection. A lack of investment in outcome level evaluations means that we are missing the opportunity to learn in a way that would inform continual development of methods and strategies to reduce risk.

Organisations that invest in analysis, outcome-oriented programming and an organisational culture that values critical thinking and continuous learning are more likely to be able to align their human and financial resources, organisational planning and decision-making processes, behind programming which has greater relevance and positive impact for people in crisis.

Through its Results-Based Protection initiative, InterAction has found through years of consultations and collaboration with humanitarian NGOs that these elements repeatedly emerge as critical success factors underpinning protection outcomes. Awareness, system-wide policies, and supporting standards and guidance are moving in the right direction, for example, as exemplified in the IASC Principal’s Statement on the Centrality of Protection, the IASC Policy on Protection in Humanitarian Action, and the Professional Standards for Protection Work.

However, even with our aspirations clearly articulated in these policies and standards, actionable information and analysis, an outcome mindset, and a learning culture remain critical gaps. There remains a great need to encourage the basic ways of working which underpin practical problem-solving. Luckily, as we like to say at InterAction, there’s no need to wait for the start of a new programme cycle or the launch of a big new initiative – just Start Where You Are.