This article promotes practitioners’ evaluative thinking to foster more complexity‐aware monitoring and evaluation for learning and adaptive management in complex and dynamic settings. Instead of simply carrying out activities based on predetermined plans or checklists, practitioners can be ‘knowledge workers’ who use evaluative thinking to promote collaboration, learning, and adaptation in service of achieving outcomes. While article focuses on development workers, its reflections on the practical application and empirical grounding of complexity‐aware and learning‐focused evaluation are also applicable to protection in humanitarian crises.

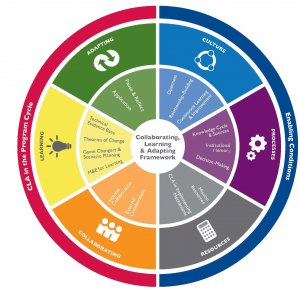

The USAID Collaborating, Learning, and Adapting (CLA) Framework

Increasingly, actors (Government, NGOs, international organizations) operating in complex environments, are shifting from predominantly linear and reductionist models of change to ones that are more dynamic, reflective, and responsive. This means understanding that humanitarian personnel are ‘knowledge workers’ who should use reflective practice to collaborate, question assumptions and ways of working, and make real time course corrections.

The article highlights the experiences of a few organizations implementing evaluative thinking and what this has meant for their organizational culture and ultimately for developing adaptive, innovative, and context-specific solutions. For example, Catholic Relief Services and their Evaluation Capacity Services places strong emphasis on evaluative thinking amongst project stakeholders, or “critical thinking applied in the context of evaluation, motivated by an attitude of inquisitiveness and a belief in the value of evidence, that involves identifying assumptions, posing thoughtful questions, pursuing deeper understanding through reflection and perspective taking, and informing decisions in preparation”.

“In our experience, promoting [evaluative thinking] is a promising practice due to its ability to: support and nurture ‘reflective practitioners who are able and willing to challenge continuously their own assumptions and the assumptions of their colleagues in a constructive way which generates new insights and leads to the development of explicit wisdom’ (Britton, 1998, p. 5); build trust between stakeholders to facilitate collective ‘sensemaking’ (Schwandt); and elevate tacit and experiential local knowledge as a critical complement to “evidence-based” knowledge. In this way, we see evaluative thinking as a way to help development staff and partners demystify theory and practice and restore their sense of purpose, curiosity, and passion for development.”

(Lederach, Neufeldt, & Culbertson, 2007)

Evaluative thinking requires:

- having a good understanding of the problem and local contextual environment

- having a good understanding of the pathways of change (causal logic)

- Inquisitiveness and possessing a desire to continuously test and learn from all levels of staff

- An appetite to take appropriate risks and apply learning to make course corrections in their work when needed.

By aligning interventions with local needs and expressed priorities, iteratively testing what works and what does not, and prioritizing learning and feedback loops, evaluative thinking can help development and humanitarian actors undertake continuous analysis, reflection and learning in pursuit of protection outcomes.

For the full article, see HERE.