Module 3: Measurement Considerations

3.1. How and why to think about outcomes measurement

Vigaud-Walsh (2020) reviewed a large number of GBV prevention projects and programs, including their associated logframes[1] and monitoring frameworks. The majority of these programs were monitoring output and activity-level indicators. In some cases, this included community perceptions of the quality of GBV prevention services. But in many, measurements were restricted to the quantity of activities conducted and the number of persons served.

There are reasons for this “retreat” to output measurement. Organizations consulted in the design of this framework cited the following challenges when it comes to monitoring outcomes for GBV work:

- Risk: Surveying community members about GBV incidence rates risks causing harm to vulnerable community members and, in some instances, to program staff. This makes it hard to collect primary data in the first place.

- Trust: Asking community members to share their perceptions of GBV requires a high level of trust in the community, which can be difficult when program staff turnover is high or when M&E staff from outside the program team are collecting data.

- Sensitivity: It is often difficult to discuss sensitive topics around sexual violence with community members, making data collection about GBV incidence unreliable even when it can be carried out without causing harm.

- Privacy and data management: Even when the data is collected in a reliable manner, it is often difficult to share sensitive case-data, or any data that could reveal the identity of vulnerable groups. This makes it difficult for M&E teams to access any results data collected.

- Cost: Robust measurement of changes in GBV incidence over time requires significant investment in measurement tools and frameworks that are very challenging to fund in the current humanitarian funding landscape. This could change if donors and implementing agencies decide to take a strategic approach to evidence generation for GBV prevention. But until it does, it will remain prohibitively expensive for organizations to measure GBV incidence in a rigorous manner that allows for attribution claims to be soundly made.

- RESPONSIBLE DATA MANAGEMENT FOR GBV PREVENTION

Recent years have seen a growth in debate and discussion about responsible data management for humanitarian actors. This has been spurred, to some extent, by increasing concerns about the capacities of state and non-state actors to survey and intercept data flows across an ever-wider spectrum, resulting from the growth of big data and its potential for exploitation. In the case of gender-based violence, this has significant ramifications for vulnerable people whose data is initially collected through more traditional means, such as the use of survey tools by humanitarian organizations conducting risk analysis, monitoring or evaluation work. For this reason, “Do No Harm” Principles must be followed for all steps of the data management cycle, from collection and storage to dissemination. Agencies are encouraged to review the guiding principles presented in the Gender-Based Violence Information Management System https://www.gbvims.com/, as well as wider principles being drawn up by the Humanitarian Data Science and Ethics Group at https://www.hum-dseg.org/

It should also be remembered that over-emphasis on measuring GBV incidence alone can be dangerous when it encourages agencies to take up harmful data collection practices, such as asking vulnerable persons to directly report incidents of GBV for measurement purposes alone. Moreover, as will be seen in this Module, there is significant value in measuring other aspects of the risk profile, such as the threats, vulnerabilities and capacities within the community that underpin the GBV risk (see the section on proxy indicators below).

These are all genuine challenges for the collection of data about GBV incidence and risk. But the impact of not measuring outcomes is significant. The drop in quality of programs without clear monitoring frameworks was noted by the DFID-funded program ‘What Works in Preventing Violence Against Women and Girls’. And the lack of evidence about what works and what does not is itself a result of this “retreat” away from measuring outcomes and sharing the learning that comes from it.

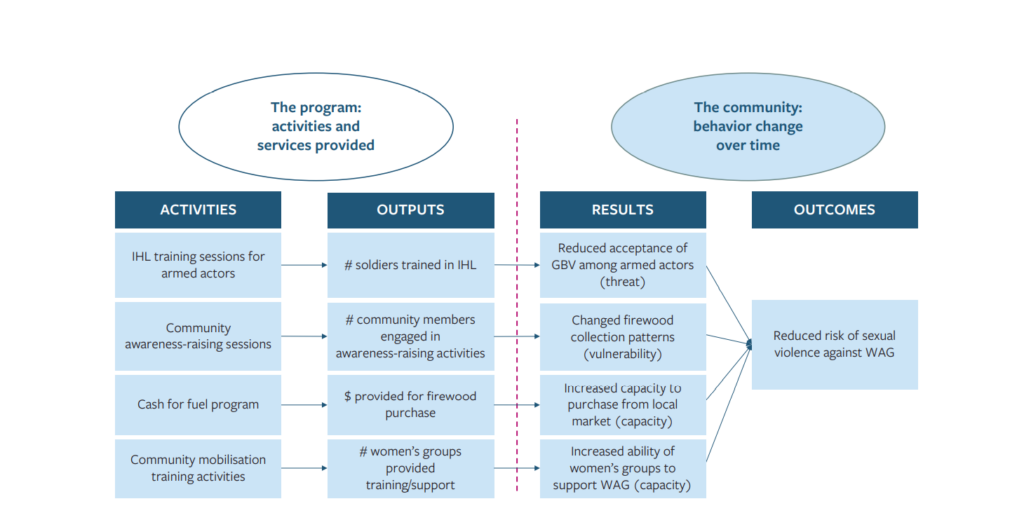

For these reasons, program and M&E staff should be clear about the importance of measuring outcomes. The simplest way to think about this is to draw a line between the changes seen that are within the “realm of the program” and the changes seen (i.e. results) that are within the “realm of the community”:

Diagram 3: What we mean by “outcomes”

Diagram 3: What we mean by “outcomes”

The example above is a fictional project logframe for a project working on the risk of sexual violence faced by IDP women and girls in an IDP camp setting. The context is hypothesized in the following way:

Background |

GBV Risk Profile

|

||

Analysis |

ThreatArmed groups threaten and perpetrate sexual violence against WAG during firewood collection. |

VulnerabilityGreatest risk of sexual violence by armed actors for: young women and girls, collecting firewood alone, during daytime. |

Capacity

|

Mitigation |

Reduce ThreatReduce acceptance of sexual violence among armed groups. |

Reduce VulnerabilityChanged firewood collection habits (e.g. large groups of mixed ages, collection at dawn and dusk). |

Increase Capacity

|

The activities include conducting training for the armed actor groups, to sensitize them to their duties under IHL and the potential implications of violations. The program also provides cash assistance to the IDPs to purchase firewood on local markets, whilst also supporting the women’s groups to increase their reach and influence in the community, and also conducting GBV awareness-raising activities within the IDP community itself. The direct outputs of these activities are measured by the number of soldiers trained, the number of womens’ groups provided with support, the cash value transferred to IDP households and the number of community members engaged in awareness-raising activities. All of this remains within the realm of the program: its activities and services provided. The results come after this, in terms of the reduced acceptance of GBV among soldiers in the armed group, the decreased vulnerability of young women and girls conducting firewood collection alone during the day, and the increased capacity of households to purchase firewood from local markets and of womens’ groups to support women and girls as they face this risk. These are all changes within the realm of the community: the beliefs, attitudes and behaviors of community members and soldiers toward GBV. Lastly, the outcome is measured in the reduced incidence of GBV committed by armed actors against women and girls from the IDP camp. By focusing on outcome-level measurement tools that help measure the intermediate results, program teams can learn about the community-level changes their activities have helped bring about. But to do this well requires planning. Designing good outcome and results indicators takes care and attention. Outcome measurement tools need to be selected that meet the information needs of the monitoring framework. And the evaluability of the program needs to be tested and considered by M&E teams before any measurements can take place. This module presents some of the main considerations to bear in mind when thinking about monitoring frameworks for GBV prevention. In particular, the following three critical elements are presented

- Indicator design: how can organizations design feasible outcome and results indicators in the face of the challenges presented above?

- Evaluability assessments: how can organizations make sure their GBV prevention program designs make effective measurement and evaluation possible?

- Outcome mapping approaches: how can organizations develop monitoring and evaluation tools to help them track behavior change over time?

3.2. Indicator development

3.2.1. Why indicators matter

Well-designed indicators allow M&E teams to measure the progress of a project towards its goal. Without clearly defined indicators, even the clearest theory of change can be hard to test.

Monitoring frameworks should include indicators across the results-chain, including indicators for outputs, results and outcomes of the activities:

DEFINITIONS BOX 3:[2]

- OUTPUT INDICATOR

A measure of number and quality of the products, goods and services which result from an activity.

- RESULTS INDICATOR

A measure of the changes in the community and lived experiences of vulnerable people directly resulting from an intervention. This can include changes in behavior, attitudes, policy and practice of individuals, groups, communities, organizations, institutions or other social actors. They should relate to the threats, vulnerabilities and community-based capacities underpinning GBV risk.

- OUTCOME INDICATOR

A measure of the changes in GBV risk faced by specific vulnerable people and groups in the community.

Prior to starting project activities, it is important to design clear indicators for each intended result and outcome. Good indicator frameworks typically mix quantitative and qualitative data types and support an understanding of how the project is influencing change over time.

But it is also worth bearing in mind that indicator-based monitoring is not the only way to measure change. “Indicator-free” approaches, like Most Significant Change and Outcome Mapping (see module 4 below for details on these approaches), make space for information being provided by community members that doesn’t necessarily fit into a list of pre-defined indicators. Tools like these encourage project teams to turn the monitoring question away from project design and towards the lived experiences of crisis-affected populations. Nevertheless, it is rare that project-level monitoring can be conducted entirely using these methods. As such, indicators remain at the core of the measurement effort for the vast majority of project-level monitoring systems.

The following sections present some of the common pitfalls faced when designing indicators for complex social change, followed by an overview of how to use proxy indicators for hard-to-measure change.

3.2.2. Common pitfalls to avoid

Global-local mismatches:

Organizations employing global theories of change often provide linked indicators to support measurement of their sector-wide ambitions. The intended outcomes at global level may include overarching goals such as tackling harmful gender norms or reducing military actors’ acceptance of sexual violence during conflict. The difficulty comes when trying to measure project-level results using global-level frameworks; or conversely when using project-level results to demonstrate change at a global level.[3]

Instead, it is important to make sure the project’s theory of change is context-specific before using it to develop indicators. This will often mean accepting that an individual project will only contribute to a small part of a global theory of change. But doing so will allow program and M&E teams at country-level to measure results against context-specific indicators that take account of local capacities and the effects of localized external actors on behavior change.

Exclusion of community voices:

Participatory indicator development can be difficult, time-intensive, and can sometimes be inappropriate on “Do No Harm” grounds.[4] This can put-off project teams, particularly when designing interventions in constrained contexts.

Nevertheless, the exclusion of community voices in the selection and design of monitoring indicators can significantly impoverish decision-makers’ understanding of the project’s results and impact within the community; as well as raising concerns about power imbalances regarding decisions about what to measure, and what not.[5]

As such, it is recommended that, wherever ethical and feasible, project teams maximize the integration of community voices when designing measurement indicators at project-level. Tools for doing this can be drawn from pre-existing participatory evaluation techniques, and adapted to fit the design and selection of indicators, e.g. by using group workshops, participatory rapid appraisal techniques, or even focus group discussions and survey tools. Indeed, even before designing indicators, these tools can and should be used, where ethically possible, while developing the risk analyses and project theory of change, as outlined in Module 2, above. Indicators should then be defined that link back to the risk analysis and theory of change.

Hard-to-measure indicators:

Some monitoring frameworks include indicators which, in reality, take several years to gather data against before a measurement can be given in confidence. Changing harmful gender norms, for instance, can fall into this category. This can be a powerful learning approach when paired with a long-term investment in measurement over time, a robust quasi-experimental methodology, and a reasonable expectation that data collection and quality will not be degraded by conflict or instability over the timeframe. But in reality, funding envelopes and timeframes for the majority of single-project humanitarian interventions exclude this level of investment.

Instead, it is recommended that indicators are selected on the basis of both relevance to the theory of change and feasibility of measurement. In particular, the following checklist is worth using before committing to collect data against an indicator for a GBV prevention project:

Indicator Feasibility Checklist

1. What would measuring against this indicator require of affected individuals and communities? Is there a risk of doing harm by measuring it?

2. Is it realistic to expect observable change in this indicator over the life-cycle of the project?

3. Is it possible to measure change in this indicator given the conflict or crisis context?

4. Does it require primary data collection? If so, are access constraints an impediment?

5. What secondary data sources can be leveraged to measure change for this indicator?

6. How often would measurements need to be taken? Can this be managed by the monitoring or evaluation team?

7. What skillsets would the monitoring or evaluation team need to measure against this indicator?

3.2.3. Proxy indicators

As outlined above, there are a number of challenges to collecting data about the outcomes of GBV prevention, given the difficulty of collecting and analyzing high quality data about GBV risk and incidence at community-level. One way to overcome these difficulties is to use proxy indicators instead.

Proxy indicators are indirect measures that are used when making direct measurements of change is not possible or appropriate.[6] Proxy indicators track changes that go hand-in-hand with the change you are trying to measure. Fossil records, for example, can be used as a proxy indicator for historical climate change: we can’t directly measure what the earth’s climate was like 4,000 years ago, but the patterns of plant and animal life recorded in fossilized form can reliably tell us about it, because it goes hand-in-hand with climate change.

Devising and testing a bank of accurate proxy measures for GBV requires more research and field validation across contexts. But proxies that organizations already use include measures such as male attitudes towards the permissibility of intimate partner violence; or the freedom of women to communicate with each other and self-organize to reduce IPV risk. These are not direct measures of intimate partner violence or sexual abuse. But they are considered to demonstrate some degree of correlation (or inverse correlation) with those forms of violence. As such, they are used by organizations seeking to measure GBV risk when direct measures are either impossible or inappropriate.

Project teams should use the risk analysis, when broken down into threats, vulnerabilities and capacities, to develop proxy indicators linked to the components of risk. Doing so will allow teams to continuously monitor changes in the risk profile to inform a continuous GBV risk analysis.

Once this is done, proxies can be developed for hard-to-measure outcomes by looking for bundles of indicators that are related to the desired change. For example, as a proxy for early/forced marriage, an organization might choose to measure the following bundle of indicators:

- Markers of community attitudes towards – and acceptability of – early/forced marriage (threat).

- Levels of economic insecurity at household-level (vulnerability).

- Demonstrated awareness of alternative sources of income for insecure households (capacity).

Or, as a proxy for physical assaults on people with non-conforming gender identities, an organization could choose to measure the following bundle of proxies:

- Markers of community attitudes towards gender identities and acceptance of violence in the public domain (threat).

- Measures of social isolation for persons with non-conforming gender identities (vulnerability).

- Demonstrations of community members to observe and intervene in emerging threats against persons with non-conforming gender identities (capacity).

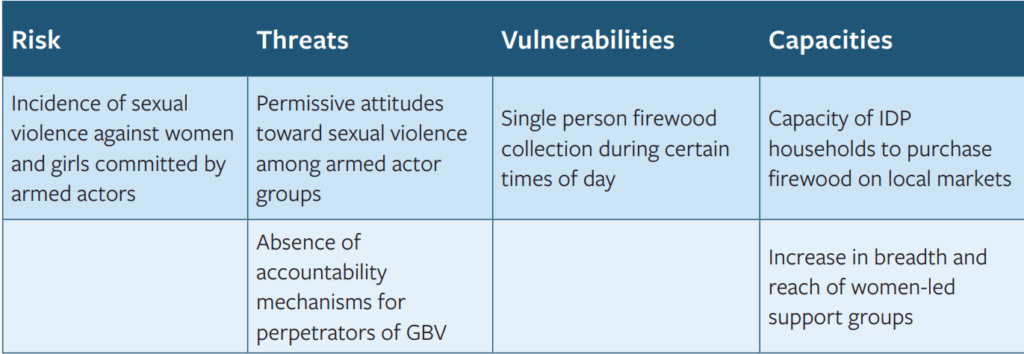

Likewise, in the fictional GBV prevention program introduced in section 3.1. above, the organization may use the following proxies to measure the risk of sexual violence against women and girls collecting firewood outside an IDP camp:

- Observed instances of accountability mechanisms being established, strengthened and used by armed groups against perpetrators of GBV (threat).

- Markers of attitude shifts towards GBV among the armed group (threat).

- Reduction in observed single person firewood collection at certain times of day (vulnerability).

- Increased financial capacity to purchase firewood on the local market (capacity).

- Increased strength and reach of female-led support groups to self-organize safer firewood collection (capacity).

By bundling together several proxy indicators in this way, whilst aiming to cover the breadth of the components of risk outlined in the risk equation in Module 1, the project team can help enhance their understanding of the hard-to-measure change in GBV risk. But, when selecting such bundles, it is important to choose indicators that go hand-in-hand with the hard-to-measure outcome, and which can work together to tell us more about what is happening at outcome level. In the examples above, the indicators “collaborate” to tell us about the background permissibility of early/forced marriage in the community, the levels of economic security driving households to engage in early/forced marriage, and the degree to which households alternative income sources are being made available to insecure households. Taken together, these facts can help to “paint a rich picture” of early/forced marriage in the community and demonstrate, over time, how change is happening and what it looks like.[7]

3.2.4. Using the Risk Equation

The proxy indicators cited above can in fact be traced back to the risk equation presented in Module 1, as illustrated below:

The point here is that, in cases where it proves difficult or inappropriate to measure GBV incidence, a well-developed risk analysis, for example using the GBV risk canvas presented in Module 1, can help provide proxy measures instead. In this case, by working through the nature of the threat, the nature of what makes community members vulnerable to that threat and the types of community capacities to mitigate it, the organization is able to broaden the range of outcome-oriented measures it has at its disposal. In cases where GBV incidence is already hard to measure, this breadth of options can be useful.

3.3 Ethical considerations for GBV M&E processes

3.3.1. GBV Guiding Principles

Throughout the program cycle, staff will undoubtedly encounter GBV survivors. Survivors who disclose an incident of GBV are often at high risk of stigma and further violence by the perpetrator or others. To safeguard against this, the survivor-centered approach is employed in all interactions with GBV survivors, including data collection for the purposes of monitoring of evaluating prevention programs.

A survivor-centered approach is a supportive environment in which survivors’ rights and wishes are respected, their safety is ensured, and they are treated with dignity and respect. It is underpinned by the following guiding principles:

Safety: The safety and security of survivors, their children, and those assisting them are the primary considerations. Safety refers to both physical safety and security and to a sense of psychological and emotional safety.

Confidentiality: Survivors have the right to choose to whom they will or will not tell their story, and any information about them should only be shared with their informed consent. Maintaining confidentiality means not disclosing any information at any time to any party without the informed consent of the person concerned. Information about a survivor’s experience of abuse should be collected, used, shared and stored in a confidential manner.

Respect: All actions taken should be guided by respect for the choices, wishes, rights and dignity of each survivor.

3.3.2. The “Do No Harm” approach

The “Do No Harm” centers on taking measures to avoid exposing people to harm as a result of our work. This means making sure that the actions we take do not create further GBV risks or any other kind of harm for survivors and others at risk. The “Do No Harm” principle includes:

- Avoiding any actions that might expose a survivor or person at-risk to acts of revenge or further violence.

- Making all communication and interactions safe and supportive to avoid the traumatization of survivors.

- Ensuring that the collection, storage, and sharing of information abides by the GBV Guiding Principles, and does not create any additional risk.

3.3.3. Ethical considerations for data collection and use

As working with survivors, or those at risk of GBV, engenders significant safety and security concerns, the research for the design, monitoring, and/or the evaluation of GBV programs—including prevention programs—must be undertaken with extreme care and sensitivity to respecting GBV Guiding Principles and the “Do No Harm” Approach. This is particularly relevant when it comes to collecting and using data.

The International Committee for the Red Cross has developed professional standards that we should adhere to ethically to manage sensitive protection information. They include, but are not limited to, collecting information for the use of protection programs, endeavoring to collect such information if the organization has the right information management system to process and store data confidentially, evaluating the scope of information to be collected in relation to its relevance for protection programs.

With regards to GBV specifically, the World Health Organization developed eight safety and ethical recommendations to be considered before researching violence against women and girls. This is applicable to all GBV-related data collection activities, including needs assessments, surveys, and the monitoring and evaluation of interventions. The eight recommendations are:

1. Analyse risks and benefits: Before collecting any data, it is important to consider both: (1) potential risks that respondents and data collectors may experience, and (2) potential benefits to the affected community and the wider humanitarian community. It is critical that the benefits outweigh the risks.

2. Methodology: Data collection activities must be safe and survivor-centered, methodologically sound and not time intensive.

3. Referral services: Basic care and support to survivors must be available locally before commencing any activity that may involve individuals disclosing information about their experiences of violence.

4. Safety: The safety and security of all those involved in information gathering is a primary concern and should be monitored continuously. Safety and security conditions should be regularly incorporated into the security protocol.

5. Confidentiality: The confidentiality of individuals who participate in any data-collection activity must be protected at all times. Data should be collected anonymously where possible.

6. Informed consent: Anyone participating in data gathering activities must give informed consent. Before collecting data, all participants need to be informed of the purpose of the exercise, the risks they may face, and the benefits (including any monetary or in-kind compensation) they can expect to receive due to their participation.

7. Information gathering team: The data gathering team must include women. All members must be selected carefully and receive relevant and sufficient specialized training and ongoing support.

8. Children: Additional safeguards must be established if children (i.e., those under 18 years old) participate in information-gathering.

For more detailed information, please see:

- World Health Organization (2007). Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Researching, Documenting and Monitoring Sexual Violence in Emergencies. Geneva. https://www.who.int/gender/documents/OMS_Ethics&Safety10Aug07.pdf

- ICRC (2009). Professional Standards for Protection Work Carried Out by Humanitarian and Human Rights Actors in Armed Conflict and Other Situations of Violence. Geneva. https://www.icrc.org/en/ doc/assets/files/other/icrc_002_0999.pdf

- CHS Alliance, Group URD and the Sphere Project (2014). Core Humanitarian Standard on Quality and Accountability. https://corehumanitarianstandard.org/files/files/Core%20Humanitarian%20 Standard%20-%20English.pdf

- IASC (2019) Guidelines for Integrating Gender-Based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Action https://gbvguidelines.org/en/

3.4. Evaluability

3.4.1. What is evaluability and why does it matter?

The term “evaluability” refers to the extent to which an “activity or project can be evaluated in a reliable and credible fashion”.[8] Projects with poorly specified risk analyses, theories of change, or monitoring frameworks, are invariably hard to evaluate in any meaningful way. By assessing our programs for evaluability during the project design stage, we can help improve those project designs themselves. This is especially important for GBV prevention given the project-design weaknesses discussed in the introduction to this framework.

Evaluability assessments are often conducted by donor agencies and INGOs prior to the commissioning of independent evaluations of their projects and programs. They are usually conducted in order to assess:[9]

- Theoretical evaluability: given the project design as it currently stands, how possible is it to measure intended results and the desired outcome? Does the project have clear objectives? Are those objectives translatable into measurable indicators?

- Practical evaluability: is it feasible to collect all the data necessary for the evaluation of the project? Are there any access constraints blocking primary data collection? Are all the key stakeholders sufficiently engaged and supportive of an evaluation at this time?

- The usefulness of an evaluation: who is most likely to use the evaluation and how? How would the evaluation complement other monitoring and research activities related to the project?

Whilst each of these questions are worth asking prior to conducting an evaluation, they are also valuable questions to ask during project design itself. This can help sharpen the clarity of the project design and highlight any areas of confusion in the theory of change. Considering evaluability at project design stage can also help M&E teams to design appropriate monitoring frameworks from the outset. And ultimately, early consideration of evaluability can be a useful means to improving the evidence-base for future project approaches, a point of particular value for GBV prevention actors.[10]

3.4.2. How to design for evaluability

Designing for evaluability means conducting project design in a manner that supports evaluability throughout implementation. Key elements to consider in this regard include:

- Basing the project design on a clear context-specific risk analysis, following the approach outlined in Module 1.

- Developing a clear theory of change including assumptions and evidence, as outlined in Module 2.

- Identifying clear and observable indicators in a manner that supports relevant data collection against them.

- Planning, and budgeting, for data collection ahead of time.

- Each of these things can help sharpen the project design. And when implemented well, can help project teams course correct during implementation.

The following section presents a quick evaluability check-list, designed for use by project teams during project design. It focuses on the clarity of the project design and the type of evidence that will need to be monitored during implementation, in order to conduct a useful evaluation. No specific evaluation, monitoring or data skills are needed to use this checklist, and the assessment is designed to be possible within the equivalent of 0.5 working days.

3.4.3. Example evaluability checklist

The checklist below is adapted from Davies (2013), ALNAP (2016) and Dillon et al. (2019). It covers key questions for project teams to consider when designing GBV prevention programs, to ensure evaluability and support the design of an appropriate monitoring system during implementation.

- Project Design

As expressed in the project and proposal documents and theory of change or logframe

- Does the project clearly define the specific types of GBV that it seeks to prevent? E.g. instead of just targeting sexual violence, does the project go further to target, say, rape of adolescent girls as a tactic of war by a specific armed group in the region?

- Has the beneficiary population been clearly identified?

- Has the beneficiary population been clearly involved in the project design?

- Are all the elements of GBV risk (including threats, vulnerabilities and community coping mechanisms) clearly identified in the project documents?

- Is the risk analysis explicitly contextualized to the specific community and crisis context?

- Has an explicit theory of change been presented, including activities, outputs and outcomes?

- Is the theory of change contextualized to the community and crisis context?

- Do the proposed activities logically relate to the intended outcomes?

- Are the proposed outcomes relevant to the GBV risk the project seeks to reduce? Are they relevant to the beneficiary population’s observable needs?

- Does the project documentation include valid indicators for each step of the theory of change (from activity, through output to outcome)? Will these indicators capture the changes that the project aims to achieve?

- Have assumptions about the roles of other actors outside the project been made explicit – including both enabling and constraining actors? Are there plausible plans in place to monitor these?

- Data Availability

Based on available project documents and current practice of in-house M&E systems

- Has the beneficiary population been engaged in the design of the data collection system?

- Is baseline data available which has been disaggregated by age, gender, ability, and other characteristics or vulnerabilities relevant to the context?

- Do credible plans exist to gather suitably disaggregated data during project implementation without causing harm or presenting risks to the affected population?

- Is the data disaggregation appropriate to the project’s GBV risk analysis and beneficiary population?

- Can project partners and/or cluster members provide relevant secondary data for project monitoring?

- Are there any specific data gaps relating to the explicitly defined indicators in the theory of change?

- Is there a credible plan to collect data against all of the indicators in the theory of change without causing harm or presenting risks to the affected population? What is the planned periodicity of data collection? Are sufficient budget, human resources and skillsets available for this task? Are there GBV services in place at the proposed site of data collection?

- Do the monitoring systems in place make space for measuring unintended consequences, pursuing open-ended enquiry, and allowing for beneficiary-led sense-making?

- EVALUABILITY: CRITICAL TAKEAWAYS

- Considering evaluability is important during project design as it helps to sharpen project designs and structure monitoring systems prior to implementation.

- It is important to consider both theoretical evaluability (how clear is the project design) and practical evaluability (how available is the data).

- Rapid evaluability assessments can be conducted with a minimal time investment and no need for external evaluation expertise – so long as the project design documents and theory of change is sufficiently explicit and contextualised.

3.4.4. Useful resources

- Davies R (2013). Planning Evaluability Assessments: A Synthesis of the Literature with Recommendations. DFID Working Paper 40. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/248656/wp40-planning-eval-assessments.pdf

- ALNAP (2016). Evaluation of Humanitarian Action Guide. London: ALNAP/ODI.

- Dillon, Christoplos and Bonino (2018). Evaluation of Protection in Humanitarian Action: an ALNAP Guide. London: ALNAP/ODI.

3.5 Outcome Mapping

3.5.1. What is outcome mapping and how can it help?

Outcome mapping is a method for planning, monitoring and evaluating projects and programs that aim to achieve lasting social and behavioral change. It was originally designed by the International Development Research Centre in Canada, with the first guidebook being published in 2001. Since then, the method has been developed and used across a wide range of development and program contexts, and has been adapted and built upon by many of the organizations using it. An online learning community has been established to help program managers learn about outcome mapping, and includes a range of useful resources for anyone seeking to learn more. The community is available at https://www.outcomemapping.ca/start-here.

Outcome mapping has a range of potential uses for organizations working to prevent GBV in humanitarian contexts, including:

- It can help program teams understand complex behavior change within a community over time. This is useful for teams who want to better understand how their activities are influencing changes in the behaviors of perpetrators, vulnerable groups, and the wider community.

- It can help teams think about the pathways to change underlying their program logic. This is useful when trying to understand how the pre-conditions and underlying factors for GBV change and evolve over time.

- It is particularly useful for mapping and observing wider changes across a community, beyond the direct intended results of the program. This can help teams understand how GBV prevention activities conducted with a specific target audience can influence wider community changes beyond the direct program participants.

But the difficulty of using outcome mapping in humanitarian contexts is time and labor resources needed to make it work; and the need to think about outcome mapping across the project cycle: from initial design stage, through implementation and final evaluation.

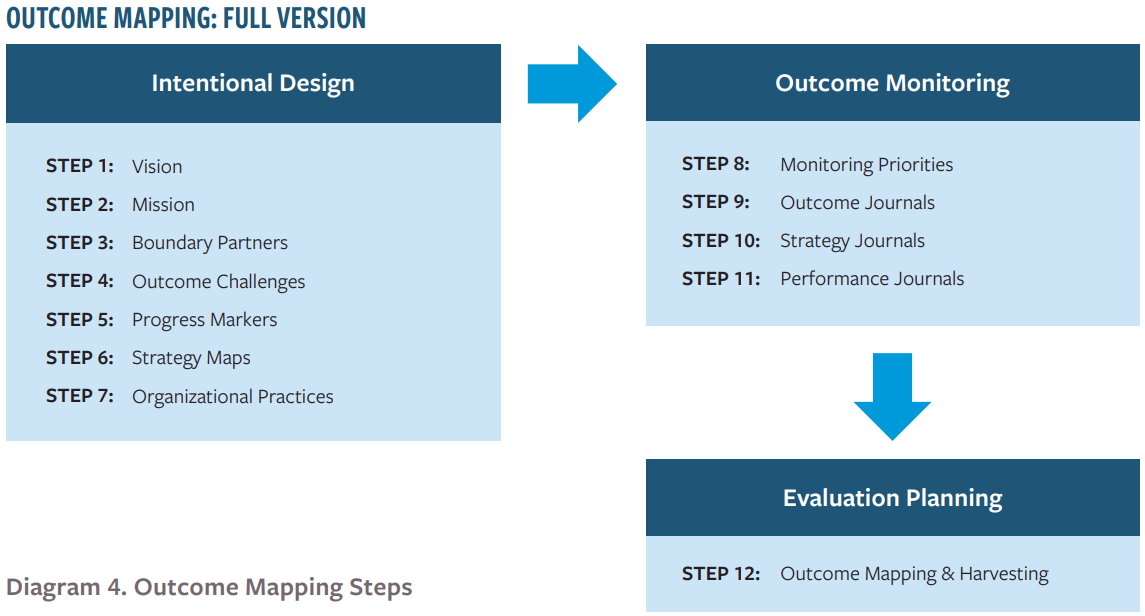

To implement a “full” outcome mapping approach, program teams need to follow each of the 12 steps outlined in the illustration below, spread across project design (stage 1) implementation (stage 2) and evaluation (stage 3):

Diagram 4: Outcome Mapping Steps

Each of these steps requires a participatory approach. For example, “Step 1: Vision” involves working with community members to identify the big-picture change that they want to achieve. This is normally a very ambitious picture, covering multiple areas of social interaction. For example, a GBV prevention team in Cox’s Bazar might have a vision such as “we want all migrants living in Cox’s Bazar to be free from the threat of all forms of gender-based violence, including intimate partner violence, discrimination based on gender norms and sexual exploitation and abuse by humanitarian workers.” Designing this vision would typically require running several workshops with community-members and program teams, working together to describe the community they want to live in. And this type of activity needs to be replicated for each of the 12 steps of the outcome mapping process.

3.5.2. A streamlined version for humanitarian contexts

The difficulty of doing this in humanitarian contexts is outlined in Module 1. Humanitarian teams typically don’t have significant time to invest in project design, with proposals often being designed in 2-4 weeks-time.

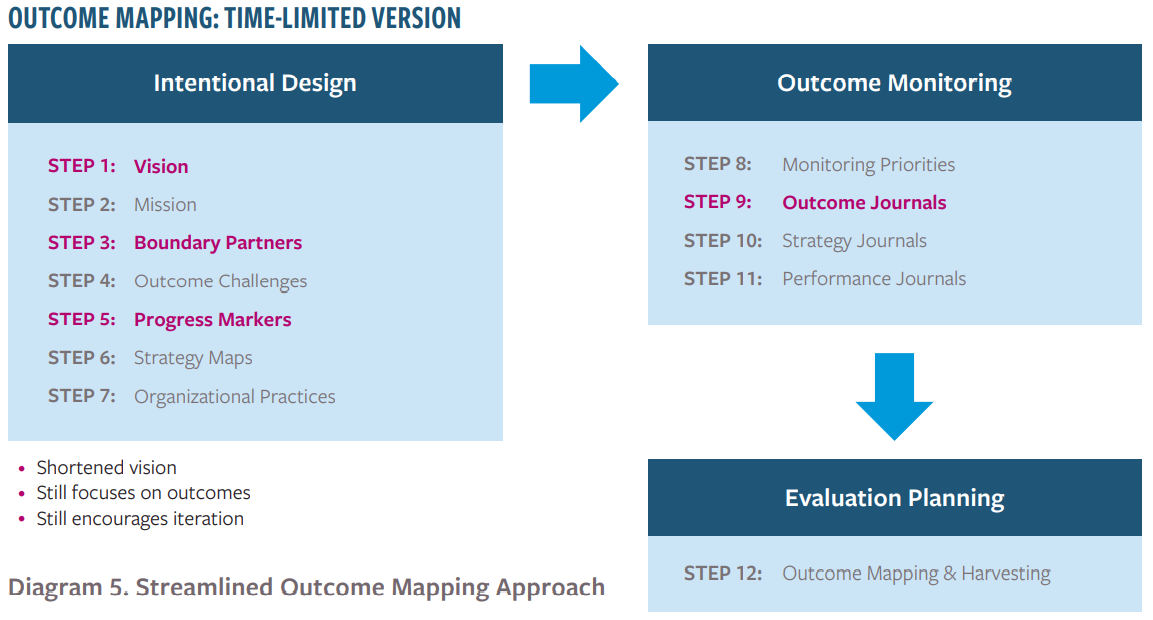

For this reason, this framework proposes the following streamlined outcome mapping approach, which isolates the key elements of most potential benefit, whilst reducing the number of steps required for successful implementation in a short timeframe:

Diagram 5: Streamlined Outcome Mapping Approach

This version includes just four steps:

- Step 1: Vision. Describing the big-picture vision that the program (or country office) wants to achieve over the medium-term.

- Step 3: Boundary Partners. Choosing a number of key program stakeholders, who will interact directly with the program activities (e.g. as participants to GBV awareness-raising workshops) but who also have influence across the wider community (e.g. through involvement in women’s support groups or men’s social networks).

- Step 5: Progress Markers. Identifying the key behavior changes within the community that will lead up to the overarching change you are trying to bring about.

- Step 9: Results Journals. Designing journal tools for boundary partners to use as a way to track the changes described by the progress markers identified in Step 5.[11]

The following sections outline each of the first three steps of this process, which should all be undertaken during project design stage or, where possible, before proposal design itself. Step 9, results journals, is covered in Module 4 below, as it relates directly to evaluation tools and approaches.

3.5.3. Step 1: Vision

The program vision is the large-scale community-wide scenario that the program wants to contribute to bringing about. It typically combines descriptions of the ideal economic, political, social or environmental situation the program is working towards. For this reason, it is best to think in terms of longer-term goals and social change. One way to do this is to link the vision to longer-term strategic planning, beyond the life-cycle of an individual program. For example, a country-team working on GBV prevention in rural Afghanistan could try to map out where they want rural communities to be in 2-3 years with regards to gender-based violence risk. Questions to ask might include:

Social Domain |

Example Questions to Ask |

| Awareness of GBV risk: | What levels of GBV awareness do you want the community to have in three years’ time? |

| Background gender norms: | What attitudes towards women and girls do you want men and boys to hold? |

| Accountability mechanisms: | What accountability mechanisms do you want local and community authorities to have in place? |

| Community-based response: | What role do you want local women’s led organizations to have by then? |

The contribution of the organization, and the individual programs that it implements over the next three years, might only be one part of this vision. But it is still important to identify the vision at design stage, particularly in protracted crisis contexts where the organization has, or intends to have, a continued presence over the medium-term.

This tool should be easy to integrate into pre-existing strategic design processes that the organization already undertakes as part of its GBV prevention work. In particular, it doesn’t require any additional data collection as such, so need not add significantly to the time or resource burden on project and program teams. Moreover, the work of defining a medium-term vision is closely related to the task of building a country- or area-wide theory of change, as outlined in Module 2, above. As such, it is recommended that teams wishing to develop a theory of change at this level of analysis try to develop something close to the vision statement outlined above as one outcome of the theory of change design process. This can then help the teams come back to the overarching vision as they adapt their theory of change over the program cycle.

One critical element of the outcome mapping approach is to emphasize participatory approaches throughout. As such, the design and elaboration of a vision such as this should ideally be done through community-based discussion and workshopping. This kind of activity can present risks of harm when discussing GBV risk with community groups. It is therefore essential to take a “Do No Harm” approach to consultations of this type.

Nevertheless, program teams are encouraged to integrate questions about the long-term vision within pre-existing community consultation activities, wherever possible encouraging community members to help co-design the long-term strategy of their organization’s activities in the communities they serve.

3.5.4. Boundary Partners

Boundary partners are key project stakeholders and partners, who will interact closely with the project activities themselves, but who also have the power to influence change across the wider community beyond the life-cycle of the project itself. Examples of boundary partners include:

- Sex workers participating in GBV prevention training and capacity-building programs.

- Senior military personnel taking part in training on the obligations of military actors under international humanitarian and human rights law.

- Community and religious leaders taking part in GBV awareness-raising activities and events.

The nature of GBV prevention work often entails that program teams already work closely with boundary partners during implementation. GBV prevention programming – its design and execution – must be inclusive, participatory, and accessible to all. This requires targeted work with specific at-risk groups, to understand their risks and to ensure that barriers to their participation are overcome. But reaching the people can be hard. They are marginalized and overlooked by others in society, or they must maintain a low profile for security purposes. Reaching them should be done in collaboration with civil society organizations and community associations that are experienced in working with them and meeting their needs safely.

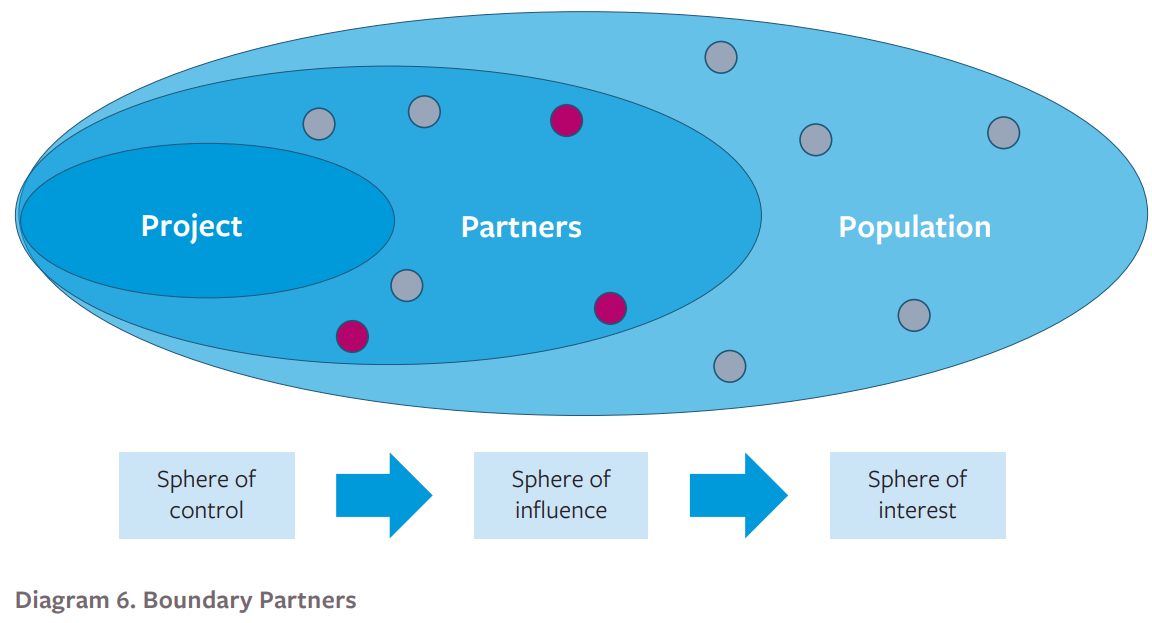

In the outcome mapping framework, boundary partners lie in a program’s “sphere of influence”. That is, they inhabit a space outside the direct control of the program teams but inside the area of indirect influence. For example, military personnel might be influenced by training activities but they cannot be controlled by program teams. But they also lie inside the “sphere of interest”, i.e., the area in which the program seeks to bring about change. The senior military personnel, for example, are part of the military structure whose behavior is of interest to the program in question.

This idea is commonly represented in visual form as below:

Diagram 6: Boundary Partners

Here, the project stakeholders are represented by dots, which lie close to the project itself (e.g. direct participants of training programs) or further away in the broader population (e.g. members of the community group who do not engage directly with the program but whose behavior is of importance to the program vision. The boundary partners are marked using red dots.

Once the program team has identified a collection of suitable boundary partners, it’s important to consult with them on the program’s proposed outcomes and activities. This is, again, ideally done before the design of any individual project proposal, following the development of the strategic vision of the organization outlined in Step 1.

3.5.5. Progress Markers

Progress markers are indicators of community-based change in behavior, attitudes, beliefs and norms, which mark the steps along the path to the broad-based change identified in the program vision. When using outcome mapping to track change in the community, its vital to have a good selection of progress markers to track. It is best to select them in consultation with the program boundary partners, and always before the program begins implementation.

To identify progress markers for a project or program, start from the immediate changes you would expect to see after community members engage in the project activities. For example, an awareness-raising activity might include pre and post-tests for participants to track the change in their awareness of GBV risk factors in their community. The first progress marker towards positive change here could be an improved score on the post-test compared to the pre-test result. This is, so to speak, something you should “expect to see” if the program is operating as planned. You can then map out further changes in the community that go beyond this base-level change, steadily moving towards the overarching change the program seeks to achieve. For example:

Type of Change |

Example Progress Markers |

| Expect to see | Increased awareness of training participants to the IPV risks in their community |

| Expect to see | Commitment of men and boys to respond differently to negative peer attitudes towards intimate partner violence |

| Like to see | Commitment of community leaders to offer support and guidance to survivors |

| Like to see | Actions by individuals to increase dialogue and awareness in the community |

| Love to see | Actions by community or local authorities to embed intimate partner violence awareness and accountability structures |

| Love to see | Broad-based agreement on the unacceptability of intimate partner violence across the community |

There are at least three critical aspects to a good collection of progress markers:

- They should all focus on changes within the community and community members themselves. It can be tempting to think in terms of project activities when thinking about the minimum standards that you “expect to see”. For example, a team might suggest “high participation levels in awareness raising events”. But this is a measure of the program output, i.e. the number of people participating in the awareness-raising activities. It is not an outcome measure. Instead, focus on what changes you expect to see in the life of the community and its members. Increased awareness of participants, for example, or commitments they make.

- They should include a number of possible steps towards change. It is impossible to know exactly how change will occur before it does. So include as many possible steps along the path as possible. When collecting data against these indicators, it is important to be open to the idea that the “love to see” changes might still happen even if the “like to see” ones don’t. Change can happen in different ways.

- They final “love to see” changes should be ambitious. The final progress markers should end with the most profound social transformation you can realistically achieve in the timeframe you are working with. These are the changes that the program was designed to achieve, and the reason for which the program was undertaken in the first place.

3.6. Bringing it all together

The purpose of Module 3 is to help program teams work alongside their M&E colleagues to identify the major measurement and monitoring considerations they need to take into account before project implementation begins. Each of the steps above should be done prior to starting activities, so that, where necessary, baseline measurements can be taken, and measurement partners (such as boundary partners) can be identified.

If done well, these considerations should equip the program and M&E teams with the following:

| 1. | A list of robust and feasible direct outcome indicators, and an understanding of how to measure against them |

| 2. | A selection of feasible proxy indicators to help measure change indirectly, preferably linked to the project’s own analysis of community-based GBV threat, vulnerability and capacity |

| 3. | A clear understanding of what the major challenges will be in evaluating the project or program, and an understanding of how to approach them |

| 4. | A clear and community-based vision of the strategic purpose of the program over the medium-term |

| 5. | A group of program “boundary partners” who can help the program team measure change in their community over time |

| 6. | A set of changes in behaviours, beliefs and norms that the program can look for as the program rolls out |