Information is a critical part of the protection environment in crisis contexts; when people have access to trusted, accurate information, they are better able to make decisions to keep themselves, their family, and their community members safe. In 2023, Internews published Information and Risks: A Protection Approach to Information Ecosystems—guidelines on how to better understand the relationship between information and protection outcomes and how to analyze information-related protection risks.

This case study explores the community-based methodology used by Internews to develop the guidelines through pilots in three countries and presents a case example using the guidelines that reflect the rich outcomes that this approach can have. It also explores the contents of the guidance and tools—how to conduct a protection analysis of an information ecosystem and introducing the Information Protection Analytical Framework (iPAF)—and how these can be used by protection actors to identify risks or enhance community engagement and outreach.

Why can information be a protection concern- and why should protection actors be interested in it?

People make decisions based on information they have access to and prioritize information from sources they trust. Information can put people at risk if it’s not accurate, timely, or trusted. Despite this, humanitarian actors often overlook the importance of information to people’s protection outcomes, instead often focusing on information related to services or behavior change.

Access to information can help keep people safe or support them to obtain services. Conversely, denial of access to information, or disinformation and misinformation, can create or exacerbate protection risks. For example, a family may choose to stay in a dangerous area, ignoring official emergency warnings in favor of information from an unreliable source. Taking this a step further, information-related protection risks can be identified—risks that are the consequence of a lack of information or risks that people face in accessing, creating, or sharing information.

Denial of access to information and disinformation have been identified as in numerous crises as tools to deprive affected communities of access to public and humanitarian services. They can foster negative coping mechanism and exacerbate other protection risks.

Internews, Information and Risks: A Protection Approach to Information Ecosystems, 2023, p. 51

Key Information Concepts to Know

- Information Ecosystem

Every community or context has an information ecosystem: the “interconnected network of various sources, channels, and platforms that facilitate the creation, dissemination, and consumption of information“. This includes traditional media, social media, organizations, governments, and individuals that contribute to the flow of information and influence how it is accessed and understood.

Within this ecosystem, individuals and communities may experience information risks, including:

- Denial of access to information

A deliberate deprivation of the ability to safely create, share, seek, and obtain information.

- Disinformation

False information which is deliberately intended to mislead or cause harm.

- Misinformation

False information spread without the deliberate intention to mislead or cause harm.

Why were the guidelines developed?

Internews recognized a gap in the understanding of how information can affect protection outcomes and how information-related protection risks are identified and acted on. Through a gradual approach, they developed the Information and Risks: A Protection Approach to Information Ecosystems guidance in 2023 with the support of USAID’s Bureau of Humanitarian Assistance.

The guidelines are a practical resource that can be used by humanitarian and protection actors, information actors, and local media who share information and engage with affected communities. They can be used with the community to identify protection risks associated with information and ways these can be mitigated, and to enhance community engagement and outreach programming.

The methodology used to develop the guidelines is outlined below, followed by an exploration of its content and tools.

This following case study is taken from a protection analyses of information ecosystem conducted using the guidelines and tools. It demonstrates the value of understanding information as an entry point to being able to address protection risks. The methodology used is outlined below, followed by an exploration of the guidelines content and tools.

Access to information and protection Risks

An information-related protection analysis was conducted by humanitarian actors in a country which had a deteriorating security situation along with food insecurity resulting from climate change, all of which impacted displaced communities living in sites in urban areas. Journalists reported having difficulty in obtaining information on the security and political situation, fearing reprisals for reporting sensitive issues.

The protection analysis showed strong interlinkages between protection risks and access to information, particularly. Over half of participants reported having difficulty finding information about the situation in their area of origin or information on missing family members, and a third having difficult accessing information on the overall security situation. In one site, nearly half of participants reported feeling unsafe after sharing information. Access to radio and television was low, limited by affordability and access to electricity. High illiteracy levels meant some people reported being unable to read and enter contact numbers to make a phone call. With these methods limited, people reported that their most accessible and trusted sources of information were face-to-face with family or friends, community leaders and religious leaders, and site managers. However, it is also true that these individuals in turn faced challenges in accessing information—due to economic or material barriers, difficulties in verifying information, or in speaking about sensitive topics without putting themselves at risk. When community members turned to family or friends back home, this presented further risks of people self-censoring information as sharing details on security is considered a risk or walking to insecure areas to get network coverage.

A consequence of this was that many people did not have access to sufficient or reliable information to be able to make decisions to keep themselves safe. Numerous participants shared stories of people having returned home thinking the security situation had calmed down but discovered on arrival that the situation remained dangerous.

Addressing these risks requires improving access to information. Solutions proposed by focus group discussion participants included the creation of safe spaces where people could access information from the radio, television, or internet and discuss issues that were important to them.

Barriers to accessing information and misinformation and rumors were also reported to be exacerbating protection risks within sites. As an example, participants shared that women were often intimidated and harassed following humanitarian distributions and forced to give up some of the items received. These issues were under-reported to humanitarian agencies, due to fears of being removed from distribution lists or of retaliation, or not knowing how to report. Recommendations toward humanitarian organizations included adapting gender-based violence reporting mechanisms and complaint and feedback mechanisms, focusing on establishing trusted relationships.

How were the guidelines developed?

The guidelines themselves were written through an iterative process, grounded in community participation and guided by a global advisory group of protection actors, information actors, and academics.

Field work was done in displacement sites in three countries, through which the concepts were tested and tools developed. In each country, Internews conducted a protection analysis of the information ecosystem using a combination of household surveys and focus group discussions with community members, key informant interviews, and roundtable discussions with local media. Each location informed the approach and tools used for the next. The cumulative learnings then informed the drafting of the guidelines and the development of the iPAF. The piloted tools were then refined and finalized. The piloted tools were then refined and finalized.

‘Hyper-local’ participatory pilots

The pilots followed a community-based participatory methodology—two with a “hyperlocal” research modality and a third exploring local media engagement. They were designed to test not only the tools but also Internews’s own theories about who can conduct this type of analysis—that it can be done by people who are neither protection nor information specialists.

In each country, a community research team was hired, led by a national researcher. The diverse teams were recruited from the targeted sites including people who were illiterate or who had not used a phone or tablet before, and all with little or no previous experience of working with humanitarian organizations. Training was delivered orally and the researchers worked together based on their skills, for example, as facilitator and notetaker for focus group discussions. In another context, the pilot focused on testing local media engagement in this type of analysis with most of the research team being recruited from community members who had worked in local radio.

The methodology was designed so that the community researchers contributed to all parts of the work. An initial five- or six-day workshop was held, where the community researchers were trained on information ecosystems and humanitarian protection, and co-developed the questionnaire tools that were to be used for data collection, fully adapting them to the context. Once data collection was undertaken and after preliminary analysis was conducted, validation workshops were held with the community participants to verify the contents and support the development of recommendations.

Questions to ask on information and protection:

Does the community have safe access to information? (Do they face risks in creating, sharing, seeking, and obtaining information?)

Does the community have meaningful access to information? (Is information accessible to all population groups based on their information needs and preferences?)

Does the community have access to accurate information?

Is the community concerned about the presence of disinformation, misinformation, and rumors?

Does the community have the tools, capacity, and resources needed to verify and analyze information, such as digital literacy or fact-checking knowledge?

What does the guidance contain?

- Module 1

For everyone—an introduction to key information and protection concepts.

- Module 2

For humanitarian (and development) actors—focusing on how to increase safe and meaningful access to information, and considerations for better coordination between different information stakeholders in a humanitarian context.

- Module 3

For protection and information actors—guiding how to undertake a protection analysis of an information ecosystem, introducing an Information Protection Analytical Framework (iPAF), and how to translate findings into recommendations and actions to mitigate information-related protection risks.

- Module 4

For journalists, media workers, and content creators working in a humanitarian context with vulnerable communities.

The guidance encourages protection and information actors to think multi-disciplinarily, understanding that some protection risks have information-related drivers (and solutions), just as they may have food security-related drivers and solutions, for example. Information providers or actors may therefore need to be part of multi-disciplinary approaches to reduce protection risks.

These modules are accompanied by a set of practical tools. Tools that can be used and contextually adapted by protection actors include: quantitative and qualitative community-based assessment tools, basic training materials on information and protection to support humanitarian (and media) actors to build the capacity of teams to better understand risks related to information, or before undertaking a protection analysis of the information ecosystem, and the Information Protection Analytical Framework.

The iPAF: A Familiar Framing for Understanding Information-Related Risks

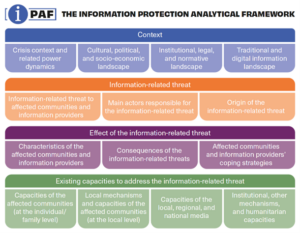

The Information Protection Analytical Framework (iPAF) is based on the Protection Analytical Framework (PAF) that was developed by the Danish Refugee Council and the International Rescue Committee with the Global Protection Cluster—all of whom sat on the Advisory Group for the project and guided the iPAF’s development.

The iPAF takes the four pillars of the PAF and draws out aspects relating to the information ecosystem to support an analysis of protection risks specific to these specific risks.

The iPAF and the accompanying assessment tools can be used to conduct a standalone protection assessment of the information ecosystem, or to ensure that analysis of information-related protection risks is integrated in protection or multi-sector assessments.

Using the guidelines

Using the guidelines

The guidelines, iPAF, and tools can be used and adapted by protection actors to:

· Better understand the “information ecosystem.”

· Conduct in-depth standalone information protection analysis.

· Integrate into existing protection or multi-sector assessment and monitoring tools.

· Enhance existing community engagement programming.

Taking the guidance forward, Internews is continuing to work on different methods for roll out and will continue to work with partners and coordination mechanisms to train on and conduct protection analysis of information ecosystems. Rollout so far has included delivery of trainings to NGO and U.N. agency staff to equip their staff to understand and apply information-related protection analysis in their ongoing work, supporting a Protection Cluster to integrate information-risk questions into a Protection Monitoring Tool, as well as sharing recommendations from the pilots and assessments conducted so far.

RBP questions to consider:

· How could these tools be used as part of an initial protection assessment to help identify ways to improve protection outcomes?

· How could these tools be integrated in monitoring and evaluation exercises to measure protection outcomes and inform program adaptation?

· How could an understanding of information-related protection risks be used to adapt and improve community engagement approaches to avoid exacerbating or creating risks?

· How could a better understanding of community preferences and risks relating to information be used to improve complaints and feedback mechanism design?

What benefit might training staff on information ecosystems and information-related protection risks have on their understanding of community decision-making and preferences and their ability to make decisions to support protection outcomes?