Determining what information people trust and why is critical for many humanitarian actors in today’s world. Accurate information, rumors, and misinformation can spread rapidly on WhatsApp groups and online, as well as in person, making it harder for people to determine what information they can trust and for information providers to reach their audience with locally relevant and reliable information. Efforts to engage with communities and share information to help keep people safe can be in vain if the information is not trusted and ignored.

People can have very low trust in reliable sources, and very high trust in unreliable sources. Internews—an NGO that supports independent media and has worked for the last 20 years in humanitarian crises helping people access quality, local information—set out to find out why. Their Trust Framework breaks down trust into core elements of proximity, accuracy, control, and intention. Analyzing these elements can help understand if trust exists, why people trust specific information providers more or less, and how to enable or increase trust.

Applying this framework can help strengthen the ways information is shared with communities and better understand people’s decision-making that affects their protection outcomes. The insights it gives may also reflect how and why people trust or distrust NGOs.

How did Internews start to develop the Trust Framework?

Internews’ work—and investigation of the underlying elements of trust—that would eventually become the Trust Framework began during the Ebola response in 2014. Misinformation and disinformation were common and dangerous; people believed incorrect information and did not trust or ignored information that might help keep them safe. Many humanitarian actors were working on information and communication with communities as part of the public health response, setting up feedback collection, helpdesk activities, and delivering messaging.

Internews started tracking rumors and working with local radio stations to try to understand where conversations were happening outside of those organized by humanitarian actors. They were interested in where misinformation and disinformation came from, how it was spread, and why people trusted it, hoping to understand how access to accurate information could be improved.

The impacts of this misinformation and disinformation were not only on people’s health outcomes, but also on the protection risks they experienced. The observations of Internews on information and trust had relevance throughout the humanitarian and public health spheres.

Building on this, Internews implemented an information response project, “Rooted in Trust,” during the COVID-19 pandemic in 15 diverse countries—from Mali and Iraq to the Amazon rainforest in Brazil. In each country, Internews conducted an Information Ecosystem Assessment and then supported humanitarian, health, and media organizations to work with communities to counter the spread of rumors and misinformation and become trusted information providers. As for its Ebola work in 2014, Internews’ findings and recommendations on information and trust were relevant not only for COVID-19 response but for any humanitarian actor conducting community engagement and information-sharing activities.

- Denial of access to information:

A deliberate deprivation of the ability to safely create, share, seek, and obtain information.

- Disinformation

False information which is deliberately intended to mislead or cause harm.

- Misinformation

False information spread without the deliberate intention to mislead or cause harm.

Accessing Trust in Information

As a starting point in each of the 15 countries, Internews conducted an Information Ecosystem Assessment. This looks at how communities find, produce, consume, and share information from different sources and the barriers they encounter in doing so.

The assessment methodology centers communities, with community members involved in selecting research questions and identifying stakeholders and uses qualitative methods with a focus on relationship-building with the communities Internews then continues to work with. Some example findings are outlined below.

Through this work with local partners and communities and building on previous work on mis- and disinformation in crises Internews was able to start a more in-depth exploration of trust. One of their main observations from discussions with communities was that the existing approaches on trust were too narrow, where multi-sector or protection assessments often ask “if certain actors are trusted.” Instead, a more nuanced understanding began to be developed that trust means different things for different people in relation to different actors.

Assessment Findings on Trust

In Iraq, mass messaging on COVID-19 had been conducted in internally displaced persons (IDP) camps by government health departments and humanitarian actors, but vaccine hesitancy remained high and rumors and misinformation about COVID-19 were widespread. The findings of the assessment in four IDP camps were that community perceptions relating to information were characterized by mistrust of the government, a perception of being abandoned in the camps without support or information about support to return, and frustration at declining service provision from both government and NGOs.

“Information deprivation, a sense of abandonment and exclusion, and a lack of trust in government institutions have gradually led to an environment that is almost immune to facts within the camps.”said Internews in their report titled, “Information Ecosystem Assessment of Internally Displaced Persons in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq During the COVID-19 Pandemic.”

Recommendations for NGOs looked at addressing a lack of trust toward the organizations which was rooted in other service delivery perceptions and changing the modality of information sharing from repeating standard messages over and over: “NGOs should…encourage participation and seek creative ways to engage IDPs in their programming. Dumping information in the camps and leaving, without establishing an effective dialogue and involving IDPs, will contribute to more confusion, not to a better and clearer understanding,” Internews’ report continued.

For humanitarian actors who were engaged in information-sharing with the community, whether on services or issues such as decision-making on return, replacement of civil documentation, or GBV prevention, these new insights could be used to understand which information sources people might trust, adjust their own information-sharing strategies, and reflect on the perception of the community members toward their organizations.

In Zimbabwe, Internews conducted an Information Ecosystem Assessment specifically with LGBTI+ people in the city of Bulawayo. Through this, they explored components that determined trust at an individual and institutional level. The assessment was implemented through key informant interviews, in-depth interviews, and focus group discussions with representatives of LBGTI organizations and LGBTI people.

Unsurprisingly, LGBTI people’s trust in, and access to, information was highly linked with the marginalization, stigma, discrimination, and sometimes violence that they face in both private and public spheres. The result of this is that many LGBTI people reported facing barriers in accessing accurate information from sources that might be more trusted or accessible to other people. However, it also meant that some capacities were higher, with strong trust relationships, solidarity, and moral support within the LBGTI community benefiting LGBTI+ people.

Proximity was a very important factor in determining trust. Faced with wider social discrimination, LBGTI people reported trusting dedicated LGBTI organizations and social media networks for information, even when unrelated to LBGTI issues. Representation and intention were also important factors. LBGTI people are usually vilified in mainstream media and, as they see themselves being portrayed negatively and inaccurately, tended to distrust mainstream media’s accuracy and question whether or why the media’s intentions would be less harmful on other issues.

Further, as people were accessing fewer information sources, their ability to ascertain misinformation versus accurate information to make the best decisions for themselves became more important. The assessment also highlighted discrimination that LGBTI people faced in accessing the healthcare system, meaning that recommendations in messaging for the general population on COVID-19 could create safety issues for LGBTI users.

We cannot trust the central government because many people in this camp her are survivors from [ISIS]. So, for example, they were told to return to their houses and the government took them in and locked them in prison for 15 years. So even if they provide [health information] to us, we cannot trust it… If the government has not even provided legal help for us, how can we trust the other information they bring?

Community Leader, IDP Camp, northern Iraq (Internews, Inequity Driven Mistrust report)

What is the Trust Framework?

Having developed a nuanced understanding of trust through work with communities in multiple countries, Internews evolved this into a Trust Framework. The framework allows NGOs to investigate the elements contributing to trust and understand why information providers (individuals, organizations, or entities) are more or less likely to be trusted.

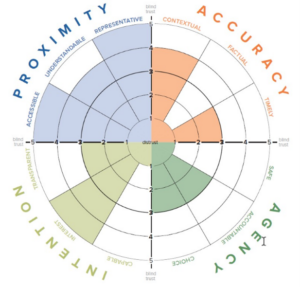

- Element 1: Proximity

Whether information is perceived to be accessible (a physical or virtual presence of the organization or entity, able to interact one-on-one or in public), understandable (a preferred language or dialect makes information easier to understand and encourages people to talk and share their perspectives in a way they are most comfortable with), and representative (do people recognize themselves in a counterpart and do they feel seen?).

- Element 2: Accuracy

Whether information is factual (it is important to be correct and transparent about information gaps), contextual (providing information that is out of touch with people’s realities may come across as uninformed and undermine the credibility of information), and timely (being fast to answer questions or to update information matters; conversely, being slow to share information can mean messages are more generic or out of date).

- Element 3: Agency:

Does the information shared recognize and reinforce people’s ability to make informed, autonomous decisions? Factors that contribute are choice (while at times there is a need to share clear directions, there is no one “right” solution for everyone and options should be shared; conversely, top-down single-issue community strategies risk patronizing people and creating resistance), if information-sharing is accountable (encouraging the audience to contribute, scrutinize, and amend with their perspectives and insights), and privacy (preserving the autonomy and dignity of people and thinking carefully about the data collected and providing clear information to the community about their rights, data processes, and options).

- Element 4: Intention

People are influenced when they believe an individual or institution cares about their best interests, and trust-based relationships can be reinforced by openness and honesty. Factors include interest (when people are suspicious about perceived interests of those providing information, they are less likely to believe it), what it is capable of achieving (the limitations or capability of a project or information should be clear to the audience, such as targeting only a specific region, topic, or group of people to avoid frustration or undermining trust), and if information-sharing is transparent (about incentives, scope, or limitations, how decisions are made, or organizational affiliation).

The Framework components should be assessed in each context with the community. Some components can be positive or negative factors in trust. For example, Venezuelan migrants in Colombia reported often not being comfortable interacting with local (mostly religious) organizations, despite their geographic proximity. They preferred to seek information online from peers, often in other countries, who they felt were more representative of themselves. However, this limited the information they received and services the were able to access, as their online communities often didn’t know about up-to-date local dynamics.

Internews, Information, trust and influence among Venezuelans in Narino, Colombia

The framework components should be assessed in each context with the community. Some components can be positive or negative factors in trust.

For example, Venezuelan migrants in Colombia reported often not being comfortable interacting with local (mostly religious) organizations, despite their geographic proximity. They preferred to seek information online from peers, often in other countries, who they felt were more representative of themselves. However, this limited the information they received and services they were able to access, as their online communities often didn’t know about up-to-date local dynamics.

Internews, Information, trust and influence among Venezuelans in Nariño, Colombia

How is Internews using the Trust Framework?

Accompanying the Trust Framework is a toolkit that can be used to assess perceptions of trust. Internews uses the Framework and its tools:

· As a core component of its Information Ecosystem Assessments, which are usually implemented in partnership with other humanitarian organizations, shared to inform information provision in a humanitarian response.

· To design programming to support access to quality, local information.

· To evaluate information-sharing and community engagement activities.

We believe that being better informed helps keep people safe… so, [we ask] what can we do in a community to organize a conversation on what their safe options are?

Stijn Aelbers, Senior Humanitarian Advisor, Internews

RBP questions to consider

· How could the Trust Framework be used to better understand information that might be driving protection risks? Could this be integrated into existing protection analysis?

· In what ways do we as protection actors interact with, provide, or influence information-sharing?

· Could the trust components be used to enhance information-sharing to address protection risks?

· How could the components of trust be used to inform protection problem-solving? Could training protection teams on the components of trust support their everyday analysis in the field?

Could the framework be used to help better understand trust relationships in the protection environment and trust between communities and protection actors?