INTRODUCTION

Despite being universally condemned by international institutions and law, children continue to face considerable risk of recruitment into state and non-state armed forces and groups. In 2021, 61 parties to armed conflict were listed in the United Nations (U.N.) Security Council Annual Report on Children and Armed Conflict as having committed grave violations of children’s rights, including the recruitment and use of children in armed forces and armed groups (AFAGs). The number of children associated with armed forces and armed groups (CAAFAG) continues to rise, and is estimated to be up to three times as high as the 93,000 U.N.-verified cases that occurred between 2005 and 2020. Much of the effort of the international community has been concentrated on the release and reintegration of current and former CAAFAG; however, less attention has been paid to the work of preventing their recruitment in the first place. There remains ample opportunity to focus on the protection outcome of reducing the risk that children in conflict face of being recruited into AFAGs by creating interventions that prevent recruitment from ever occurring.

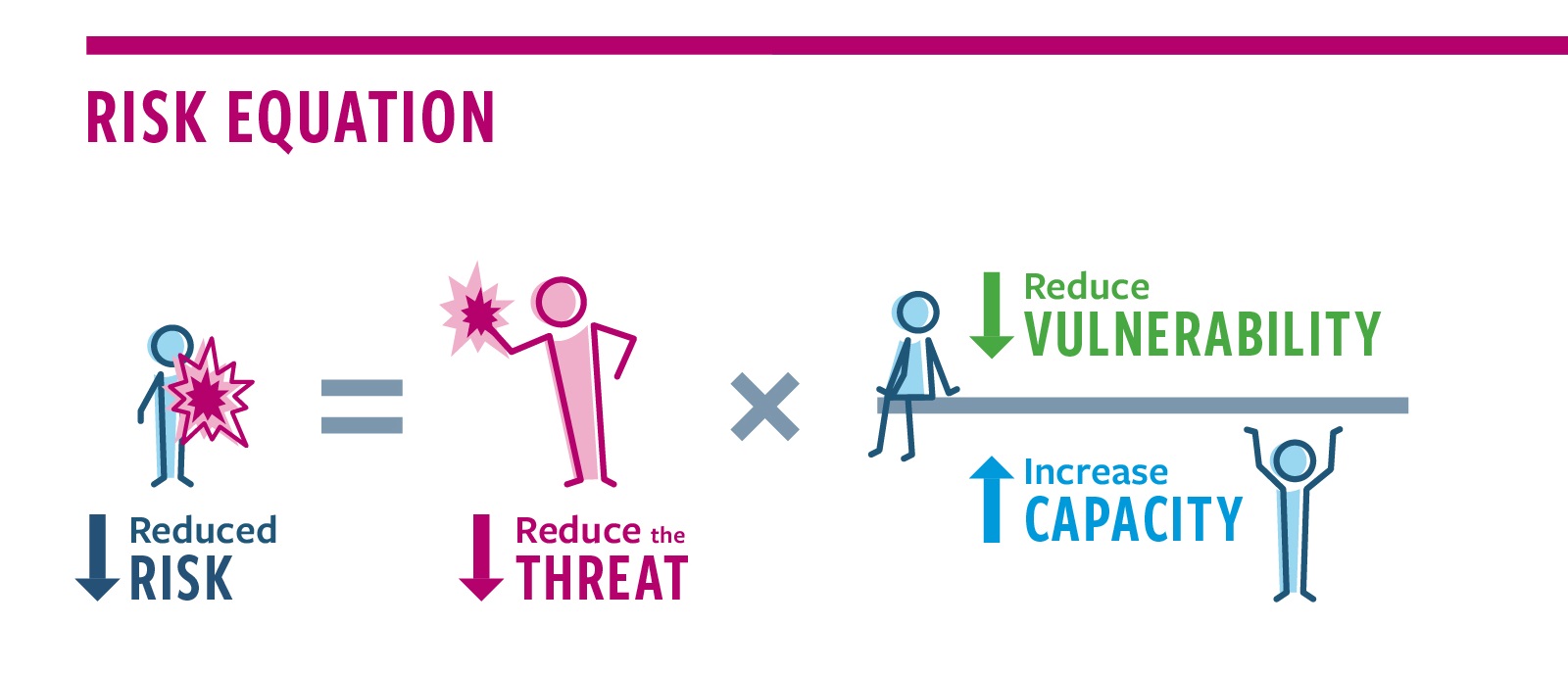

Protection risks, including the recruitment of children to AFAGs, are inherently context-specific and require in-depth analysis of local dynamics to pinpoint specific opportunities to reduce risks. Using the risk equation below, we can analyze the various components that contribute to a reduction in the risk of child recruitment. A threat represents the source of the risk. In this case, it is an armed group who recruits children. Vulnerabilities are the distinct factors that make people susceptible to a threat; for example, groups may specifically target male children who are out of school. Capacities represent the individual’s or community’s ability to mitigate that threat; for instance, the community may develop a coping mechanism to send their male children to boarding school in another region. Therefore, if we want to reduce the risk of child recruitment, we can work to reduce the threat of AFAGs recruiting children, reduce children’s vulnerabilities to the specific threat, and increase community capacity to overcome that threat.

This paper is structured to analyze each component of the risk equation as it relates to child recruitment and to feature case studies of programming that have successfully addressed each component. By utilizing the risk equation to analyze the interconnected factors related to child recruitment, we can design programming that not only ensures that equal attention is given to prevention, recovery, and reintegration efforts, but also adopts more integrated approaches across the three components.

REDUCE THE THREAT

Armed forces and other groups (e.g., gangs, paramilitary) who recruit children into their ranks are the primary threats fueling child recruitment.These threats range from forced to ‘voluntary’ recruitment, including abduction, coercion, social pressure, and financial incentives. AFAGs may recruit children for a variety of reasons, from convenience and cost reduction, to instilling fear in civilian communities. Analyzing these mechanisms and motivations for recruitment are critical to designing programming that can effectively deter AFAGs from recruiting children, and therefore, reduce the overall risk of recruitment. Several deterrent strategies are already being employed.

Threat: the source of the risk. Who is the perpetrator? In this case, an armed group who recruits children.

U.N. MONITORING AND REPORTING MECHANISM

In 2005, the Monitoring and Reporting Mechanism (MRM) on grave violations committed against children in times of armed conflict was established through the adoption of U.N. Security Council Resolution 1612 to deter abuses by armed actors against children, including their recruitment into AFAGs. The MRM functions by establishing task forces in countries where parties to conflict have been identified as having committed at least one of five “trigger violations” against children. The MRM gathers evidence of further violations and advocates for a response. Most notably, the MRM serves as an accountability tool by documenting perpetrators and their violations in the United Nations Secretary-General’s Annual Report to the Security Council on Children and Armed Conflict (SGAR-CAAC). This “naming and shaming” approach can be a powerful means of engaging AFAGs and influencing them to change their behavior, due to the risk of reputational damage or threat of sanctions. To be removed from the Secretary General’s report, a perpetrating AFAG must complete an action plan negotiated with the U.N. to halt current violations, prevent future violations, and mitigate harm caused by past violations. Since the creation of the MRM in 2005, the U.N. has successfully engaged 31 AFAGs to create 38 action plans. Twelve groups have completed the requirements of their action plans and were subsequently removed from the list. Overall, the MRM has contributed to the prevention of ongoing recruitment of children into these AFAGs and the release of more than 150,000 children.

MRM SUCCESS STORY: CHADIAN NATIONAL ARMY

The Government of Chad (GoC) was first included in the Secretary General’s annual report in 2006 for the recruitment and use of child soldiers by the Armée Nationale Tchadienne (ANT). According to U.N. figures in 2007, between 7,000 and 10,000 children may have been used as fighters or associated with Chadian and Sudanese armed opposition groups and the ANT. After halting the recruitment of children in 2010, the government signed an action plan with the U.N. in 2011 to formally end the practice. Over the next two years, the GoC worked closely with UNICEF to create child protection units, screen over 3,800 troops for minors, and institute punitive measures for recruiters of children within the ANT. In 2014, the Secretary General announced that the GoC had fully implemented its action plan and that no children had been identified among the ANT. The GoC was subsequently de-listed.

Despite these successes, the MRM has been subject to criticism over claims of politicization, whereby certain groups may be listed or de-listed from the SGAR-CAAC, or blatant violations disregarded, due to political interest or influence. In 2018, for example, the Secretary General delisted the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen despite documented intentional attacks on schools and hospitals. In relying on the MRM as a deterrent, practitioners should be aware that the listing of an AFAG, and negotiation and implementation of action plans, do not occur in a vacuum, but rather are impacted my local, national, and international politics.

NEGOTIATING WITH NON-STATE ARMED GROUPS

The MRM has also been criticized for failing to bring non-state armed groups (NSAGs) to the table. Although NSAGs are legally bound to respect international law, including the Convention on the Rights of the Child, some do not feel compelled to comply since they are not officially parties to these treaties and do not have a seat at the table. Some NSAGs, particularly those seeking political recognition, may see reputational value in participating in the MRM; however, governments may be reluctant to allow U.N. agencies to be in contact with NSAGs operating on their soil for fear of legitimizing their status. Other NSAGs may view the U.N.—and by extension, the MRM—as inherently biased and political and therefore resist engagement.

Due to these challenges, NGOs may be better placed to engage with NSAGs to stop or prevent their use and recruitment of children in hostilities. Notably, Geneva Call has developed a Deed of Commitment for the Protection of Children from the Effects of Armed Conflict, which are unilateral declarations that outline the party’s obligations to adhere to international standards and humanitarian norms. The signing of this document by an NSAG represents a commitment to ending or “prohibiting the use of children in hostilities, to ensuring that children are not recruited into their armed forces, and to never compelling children to associate with, or remain associated with, their armed forces.” Through engagement with Geneva Call, 29 NSAGs have signed the Deed of Commitment, and others have implemented parts of the Deed of Commitment and other child protection safeguards to varying degrees.

NSAG ENGAGEMENT SUCCESSSTORY: KNU/KNLA MYANMAR

The Karen National Union/Karen National Liberation Army (KNU/KNLA), an NSAG in Myanmar, had used and recruited children in various capacities since the early days of the conflict in the 1950s, with an uptick in child recruitment in the late-1990s and early-2000s. In 2003, the group attempted to limit this practice, issuing a directive that “The Karen revolution shall also appreciate international laws, protect the rights of children and respect the rules followed by many countries,” including the prohibition of the use and recruitment of children. Despite several attempts to enforce the directive, the NSAG continued to recruit and use children, leading to their listing in the SGAR-CAAC report. Recognizing the willingness of the KNU/KNLA to abolish its practice of child recruitment, Geneva Call partnered with the Human Rights Education Institute of Burma (HREIB) beginning in 2010 to engage the KNU/KNLA in dialogue. Following training sessions regarding CAAC, the KNU/KNLA agreed to sign a Deed of Commitment in 2013. Geneva Call continued to provide ground-level trainings to increase awareness of international laws and obligations regarding CAAC and decrease the prevalence of child recruitment and their indirect and direct use in hostilities.

ENAGING THE RANK AND FILE

While formal pledges represented by the MRM action plans and Geneva Call’s Deeds of Commitment have served as effective tools for changing the policies of AFAGs, compliance by local commanders can be undermined by lack of awareness and resources.

As discussed in the examples of the ANT and KNU/KNLA, officials had claimed to cease the recruitment of children long before the practice actually ended among their ranks. The KNU/KNLA argued that this was because its troops lacked a basic understanding of IHL and expectations regarding how to alter their recruitment procedures and demobilization of children already within their ranks.

Assessing the gaps in translating policy into practice is critical in the design of interventions that aim to reduce the threat of AFAGs involvement in child recruitment. Practitioners such as CIVIC and ICRC have deep experience conducting trainings and sensitization campaigns on IHL principles, supporting the design and dissemination of Codes of Conduct, and advocating for the establishment of concrete internal accountability mechanisms. These activities are often best done in direct collaboration with AFAGs to ensure buy-in and sustainability.

RANK -AND-FILE ENGAGEMENT SUCCESS STORY: MILF, PHILLIPINES

The Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) has operated a separatist insurgency in Mindanao, Philippines since the 1970s, and was first listed in the SGAR-CAAC annual report in 2003 for the use and recruitment of children. In 2009, the MILF signed a U.N. action plan to end the recruitment of children, release children in its ranks, and prevent future recruitment. However, implementation of the action plan was largely dormant until 2014 when the MILF agreed to a Road Map to completion, including a large-scale awareness-raising campaign on the rights of children, and the MILF’s Code of Conduct, which targeted rank-and-file members and the broader community. The Bangsamoro Islamic Women’s Auxiliary Brigade (BIWAB), an all-female supplementary force, was particularly instrumental in shifting attitudes and practices within the MILF, given their identity as both soldiers and mothers. The BIWAB played a central role in the planning and facilitation of awareness-raising sessions. In 2017, the group released its remaining child soldiers and was de-listed from the SGAR-CAAC report.

REDUCE VULNERABILITY

Children are widely known to be particularly vulnerable to many forms of violence during armed conflict due to their inherent emotional, mental, and physical immaturity that limits their capacity to evaluate important events, decisions, and their consequences; therefore, they are put at increased risk of predatory practices, including recruitment into AFAGs. Even if they are released, CAAFAG may face risks of re-recruitment due to struggles with mental health, social stigma, or lack of viable livelihood opportunities. These vulnerabilities are not universal across contexts, nor are they universally experienced by all children in armed conflict. Programs that seek to reduce the vulnerability of children in armed conflict should undertake rigorous risk analysis to ensure that interventions are adapted to the unique needs of children and their communities. Nonetheless, several approaches have begun to produce results across contexts.

Vulnerability: factors that make people susceptible to that particular threat. Who is more likely to face the threat of child recruitment?

PSYCHOLOGICAL WELLBEING

The importance of mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) services for rehabilitating recently released CAAFAG or children formerly associated with AFAGs has been well-established, and organizations almost always include some level of MHPSS services in demobilization and reintegration programs. Existing research also suggests that there may be a connection between mental health and child recruitment. The research posits that recruitment of CAAFAG is associated with depression and anxiety, memories of past violence and loss, and fears about the future. By extension, the inverse may also be true, that reducing this vulnerability may help prevent the recruitment of children into AFAGs in the first place or from re-joining after release.

In line with this hypothesis, War Child has developed a set of programs for children in conflict-affected areas, known as “I Deal.” Through various participatory and child-friendly methods—including music, role plays, and games—I Deal helps children to cope with the aftermath of violence, develop skills to deal with future trauma, and prepare for a productive post-conflict life or life in protracted crises. The methodology has been implemented by War Child, Plan International, and other protection actors with children who have experienced armed violence across diverse contexts, including South Sudan, Columbia, Lebanon, and Central African Republic. An exploratory outcome evaluation indicated promising results with participating children demonstrating improved social and emotional coping skills—including conflict resolution and collaboration skills—and improved self-confidence. In some cases, it helped reduce levels of psychosocial distress. However, the evaluation also indicated the importance of further contextualization of the I Deal program, recognizing that “exercises should be reviewed and adapted with local facilitators during their training, and an assessment should be made of children’s psychosocial needs, and the risks, local resources and coping mechanisms at community level before implementation begins so that these factors can be incorporated into the implementation plan.” These assumptions should always be tested prior to the design of activities to understand which vulnerabilities are present and how they manifest locally. While additional evidence is needed to demonstrate a causal link between the provision of MHPSS services to children and the prevention of their recruitment into AFAGs, such programming has the potential to reduce key vulnerabilities.

SOCIAL ACCEPTANCE

Social factors also play a considerable role in the motivations of children to join, stay, leave, or return to AFAGs. Research by IRC in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Central African Republic found that community or peer pressure was often involved in initial recruitment of children, positive or negative social dynamics within the AFAG relative to those at home affected their desires to return, and social stigmatization was a critical reason for children to seek re-recruitment. Furthermore, research by Child Soldiers International found that girls formerly associated with AFAGs not only face unique stigmatization due to community assumptions that they were sexually promiscuous or sexually compromised, but also that reintegration programs consistently fall short of addressing these gender-specific barriers to social acceptance. Practitioners should therefore aim to undertake context-specific risk analysis that includes an assessment of the social dynamics related to recruitment, and then design programming that addresses this potential vulnerability by promoting meaningful community and social acceptance.

Protection actors have begun developing methods to promote social acceptance and reduce the vulnerability of children to recruitment or re-recruitment. For example, Child Soldiers International has developed a “Practical Guide to Foster Community Acceptance of Girls Associated with Armed Groups in DR Congo” to offer practical ideas and good practices based on past experiences of reintegration programming. The guide recommends a range of interventions targeting girls released from AFAGs, as well as the communities into which they seek to reintegrate, including awareness-raising sessions, welcome ceremonies, vocational training, educational support, and community listening sessions in a way that reduces stigmatization and rebuilds social relationships. The research found that “improved community acceptance was associated with reduced depression and improved confidence and increased prosocial attitudes regardless of violence exposure.”

SOCIAL ACCEPTANCE SUCCESS STORY: NIGERIA

Since 2009, Northeast Nigeria has witnessed a brutal uprising by the armed opposition groups, Jama’tu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad and Islamic State West Africa, otherwise known as Boko Haram. These groups have recruited children as combatants; used children in support roles as cooks, load carriers, and spies; raped and forced girls to marry its members; and committed other grave violations against children. UNICEF reported that between 2013 and 2017 more than 3,500 children, most aged 13 to 17, had been recruited by Boko Haram and other armed groups operating in northeast Nigeria.

In 2019, the local organization Women in New Nigeria (WINN) received a group of more than 20 girls in Dikwa town who had been rescued from Boko Haram by the Nigerian military. WINN provided the girls with holistic services to promote their reintegration—including referrals to mental health services, vocational training, and start-up support to set up shops in the local market—and sensitization campaigns aimed at reducing social stigmatization. In particular, WINN conducted awareness raising sessions to explain the diverse factors driving child recruitment and to encourage them to do business with the girls. WINN also paired the girls with apprentices whom they trained in their selected vocations. These apprenticeships empowered the girls by placing them in the role of teachers and promoted community acceptance by creating space for them to build new relationships and contribute positively to the community.

An assessment by WINN found that several of the girls ultimately returned to Boko Haram because of feelings of stigmatization in Dikwa town and lack of access to free food. However, those who remained attributed their success to feelings of freedom and empowerment. The girls noted that they had communicated with others still living with Boko Haram to share news of their successful reintegration, sparking the interest of other girls to seek means of escape.

FAMILY SUPPORT

As the primary protection actors in a child’s life, parents and other family members ideally function as barriers between children and the AFAGs and broader conflict around them. However, when these relationships are weak or a child becomes separated from their family, they may turn to AFAGs to provide for their immediate needs of food, shelter, and protection. As a result, children with unstable family circumstances—including household poverty, mistreatment, and particularly orphanhood—are often among the most vulnerable to recruitment by AFAGs. Similarly, weak family connections have been tied to the re-recruitment of former combatants. Inversely, family care and support has been found to be “among the most important protective factors in the psychosocial adjustment and mental health of returned CAAFAG.”

In response these vulnerabilities, IRC and the Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action developed a resource pack called “Growing Strong Together: A Parenting Program to Support the Reintegration of Children and Prevent their Recruitment.” This resource pack offers evidence-based curricula and tools that aim to develop the skills of parents and caregivers to provide their children with a supportive environment, thereby reducing their vulnerability to recruitment into AFAGs. Another common intervention to reduce family separation is family tracing and reunification (FTR) processes, which aim to locate a child’s family and reconnect them. In the interim, organizations such as World Vision may place former CAAFAG in a foster family in the community or, as a last resort, in a temporary care center that can provide them with a supportive environment.

Capacity: an individual’s or community’s ability to mitigate a threat. What are community members currently doing to mitigate or reduce threats?

INCREASE CAPACITY

Although children in conflict experience numerous vulnerabilities that place them at heightened risk of recruitment by AFAGs, many others are able to resist or avoid recruitment due to existing individual and community capacities. In many cases, the same factors that, when weak, lead to vulnerability and increased risk, may contribute to resilience and reduced risk when they are robust. For example, while poor mental health, social stigmatization, family rejection, and lack of livelihoods may act as vulnerabilities, strong mental and emotional wellbeing, social and familial acceptance, and economic empowerment can all also serve as protective factors. As described in the 2022 Primary Prevention Framework for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action, primary prevention activities aimed at addressing the root causes of recruitment for children within a given population are often highly ethical and cost-effective approaches to reduce the likelihood of children becoming vulnerable originally and experiencing harmful outcomes as a result.

Education and Vocational Training

Educational support and vocational training are often the centerpieces of reintegration programming targeting CAAFAG. The U.N. Integrated Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration Standards assert that “The higher a child’s level of education, the more their reintegration is likely to succeed.” However, missed years of education may create functional and social barriers for CAAFAG to reenter school and, by extension, obtain productive livelihoods. Rather, research by the International Labour Organization (ILO) found that accelerated learning and alternative educational opportunities—such as literacy and numeracy courses, and life skills and vocational skills training—can help children achieve work readiness in a way that facilitates their economic reintegration. There is also anecdotal information to suggest that increased livelihood capacity improves social acceptance, as CAAFAG are seen to contribute income to their families and a service to the wider community. Further, comparative case studies of two children in the DRC by the ILO demonstrate how household poverty contributed to their initial recruitment into AFAGs, while their access, or lack thereof, to employment determined the success or failure of their economic reintegration and willingness to rejoin.

In response to existing programmatic gaps, the ILO developed the “How-to’ guide on economic reintegration of CAAFAG” to help practitioners bolster the capacities of CAAFAG and other vulnerable children in conflict-affected contexts, and thereby reduce their risk of recruitment into AFAGs. The guide presents ten interconnected modules and practitioner resources and tools for the full process of registration, market assessment, vocational counseling and training, long-term mentorship and support, and social protections. It also addresses the importance of victims acquiring voice, representation, and community participation. The approach has been implemented in Chad, the DRC, Nepal, South Sudan, Somalia, and Burundi, among others. Research on ILO’s intervention in Burundi found that 95% of former CAAFAG who had participated in the project were employed several years later, and that there were no notable differences in their socio-economic integration as compared to never-recruited peers.

Community-Based Child Protection Mechanisms (CBCPMs)

Community-based child protection mechanisms (CBCPMs) also serve as a critical local capacity for preventing the recruitment of children to AFAGs. As defined by Plan International, a CBCPM is “a network or group of individuals at community level who work in a coordinated manner towards protection of children from all forms of violence…[that] can be endogenous or externally initiated and supported.” An essential function of CBCPMs is their identification, monitoring, and intervention in cases of vulnerable children and families to prevent them from experiencing harm, including recruitment into AFAGs. By proactively monitoring the safety and wellbeing of vulnerable children and families, CBCPMs can quickly respond to threats that they face and prevent abuses from occurring. Some CBCPMs have directly negotiated with recruiters and other perpetrators to protect children from recruitment and agree upon reparations to families impacted by child recruitment. Because CBCPMs are comprised of community members and leaders, they often experience increased legitimacy and intimate knowledge of the community, as opposed to mechanisms operated by INGO humanitarians. Nonviolent Peaceforce (NP) has experience supporting CBCPMs, which it calls Child Protection Committees (CPCs), across Sri Lanka, South Sudan, and Iraq. Based on continuous context analysis and community consultation, the CPCs are tailored to the context in terms of the number and profile of the members, training topics, and the specific prevention and response activities implemented. In all cases, NP supports the CPCs to understand and map risks facing children in their communities, monitor changing dynamics, plan protection strategies, and coordinate with relevant local and national child protection stakeholders. In some cases, NP also provides protective accompaniment aimed at deterring violence against the CPCs, so that they can effectively conduct their activities.

CBCPM SUCCESS STORY: SOUTH SUDAN (NP)

As the war in South Kordofan State, Sudan resumed in 2011, thousands of Nuba refugees fled to Yida camp just across the border in South Sudan, which reached over 70,000 residents by 2013, of which over 70% were children. Yida camp became a fertile recruitment ground for the armed opposition group, Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), with particular targeting of boys from the Angolo and Shat tribes to fight in South Kordofan. CPCs documented a total of 186 children between the ages of 12 and 18 missing from the camp, noting that many cases go unreported. Children who escaped during 2014 and returned to Yida described witnessing or being victims of abuses, including gang rape. As of late 2014, JEM members were still reportedly accessing the camp, often disguised as traders, and families were afraid they might kidnap their sons again.

In 2013, Nonviolent Peaceforce (NP) entered Yida camp and began supporting the refugee community as they self-organized to protect vulnerable children. In consultation with the refugee council, tribal leaders, and community members, NP established a child protection committee (CPC) in each camp block consisting of 15 volunteer members (8 women and 7 men), including community leaders, teachers, nurses, elders, women leaders, and community police. NP provided the CPCs with training on child protection in emergencies and supported them to develop action plans. The CPCs conducted ongoing monitoring of new mobilization and recruitment activities by JEM, warning the community of periods of increased risk. They also conducted awareness raising campaigns on how to prevent child separation, abuse, and exploitation, and identified vulnerable children for referral to NP and other protection actors.

The CPCs were also involved in successful advocacy efforts to secure the release of children in JEM’s ranks and prevent the re-recruitment of others. In 2014, CPC members lobbied the local JEM commander to release several children who had been recruited from Yida, ultimately succeeding in returning four children to their families. In 2015, the CPCs had identified 74 unaccompanied Shat boys and three Angolo boys who had escaped from JEM and were roaming around the Yida market. They lobbied the Paramount Chief, who was also from the Shat tribe, to temporarily accommodate the boys in his home until a long-term solution could be found, while NP provided them with in-kind support, such as blankets and reintegration packages.

Although NP halted its work in Yida in 2015 and the threat of child recruitment by JEM significantly reduced in the following years, a protection executive body incorporating members of the CPCs remains operational.

CONCLUSION

As thousands of children around the world remain associated with AFAGs, prevention of child recruitment continues to be a critical goal. However, this report has demonstrated that by using the risk equation to identify context-specific threats, vulnerabilities, and capacities, prevention of child recruitment is possible. This report has also highlighted the numerous existing programmatic approaches and tools already in use by practitioners to reduce the risk facing children in conflict-affected contexts. To build on these good practices, practitioners should:

- Build context-specific risk analysis of the threats, vulnerabilities, and capacities related to child recruitment into the design and adaptation of existing and new projects.

- Design projects to address at least one component of the risk equation and, where possible, think holistically across the three components to maximize the potential for risk reduction.

- Generate new evidence to fill existing gaps in the causal logic between programmatic interventions and risk reduction related to child recruitment.

CLICK HERE TO EXPLORE OTHER CASE EXAMPLES OF RBP IN ACTION

READ MORESign-up

"*" indicates required fields