The author confirms that the views and opinions expressed in this publication are entirely their own. They do not in any way constitute the official view or position of the ICRC. The author confirms that every effort has been made to comply with their ongoing duty of discretion regarding activities undertaken during employment with the ICRC.

Case Example: A small community in a disputed area faced consistent threats from landmines and frequent shootings by armed actors. As a result, the government stopped operating public services, including the local bus network, and many young people fled. The most vulnerable individuals, including the elderly and those without the means to escape, were left behind. If they needed to see a doctor or seek other services beyond their immediate neighborhood, they were forced to walk five to 10 kilometers, exposing themselves to potential landmines and crossfire.

A humanitarian INGO sought to address these protection risks by providing small grants to buy buses and negotiating with the armed actors present to try to reduce shootings. When the INGO presented their plan to the local community, they responded that they would prefer for the state to restore the bus service. As a result, the INGO stepped back and the community stepped forward. Community representatives advocated to the Ministry of Transportation to resume bus services, and following a reevaluation of the security situation, the ministry obliged. The community representatives further advocated to the armed actors to ensure the safe passage of buses, which the armed group agreed to. By asserting their own solutions, the community achieved desirable and sustainable protection outcomes.

As demonstrated in this example, impactful results-based protection often relies on putting people at the center of humanitarian action, not only consulting them to understand their needs, but trusting them to define and implement their own protection risk reduction strategies. The People-Centered Approach (PCA) is a protection programming model aimed at guiding humanitarian organizations to deliberately create space for genuine engagement of communities in a way that puts their concerns, capacities, rights, and dignity at the heart of their programming.

The PCA is a participatory, area-based approach that aims to generate integrated protection responses working directly with people for greater relevance, effectiveness, and accountability of programming in humanitarian settings. While humanitarian programming tends to rely on needs assessments as the basis for the design of activities, the PCA adopts a threats-based analysis that focuses on people’s concerns and priorities as a way to guide them in the development of their own protection strategies to reduce these threats and achieve meaningful protection outcomes. The PCA works collaboratively with community members to identify multi-disciplinary approaches that harness the complementary expertise and profiles of diverse actors. The PCA offers a way to operationalize the Centrality of Protection and ensures that accountability to affected populations is at that core of all interventions. The PCA is realized through a set of processes and principles that recognizes the agency of communities throughout all stages of engagement.

Since 2015, Marta Pawlak has worked for various international humanitarian organizations and has been continuously inspired to design programming directly with communities. She subsequently began facilitating workshops on the PCA for other field practitioners across diverse contexts—training over 750 people to date—which enabled her to refine the approach. Building on these experiences, Marta consolidated the principles and processes into the PCA roadmap. She currently works for ICRC and is continuing to support the expansion of the PCA model in her private capacity.

THE PCA ROADMAP

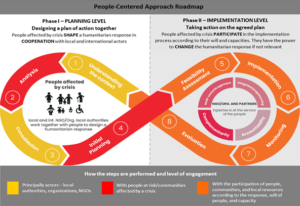

The PCA Roadmap proposes an eight-step process constituting two phases for planning and taking action. Community stakeholders are involved in every step of this Roadmap. The process starts with organizations developing a basic understanding of the context, including the conflict dynamics relevant stakeholders, and culture. Organizations and communities then seek to analyze the specific threats, vulnerabilities, capacities, and underlying causes that affect local people through a participatory workshop. In the consolidation step, organizations triangulate this analysis with secondary sources and assess which approaches they may or may not be able to support, due to internal mandates and constraints. Organizations and communities then collaborate on developing initial planning during another workshop, ensuring that all actions abide by do no harm principles and delegating roles and responsibilities. Organizations and communities conduct feasibility assessments to ensure that all proposed actions are actionable within the current context. Finally, all actors implement the identified multi-disciplinary activities according to their resources and abilities. Organizations conduct regular consultations with community members to monitor progress and adapt their activities as needed. Organizations should also evaluate the success of the approaches and share the findings back with communities to enable continuous improvement of protection responses.

The above steps that support PCA can be fully achieved only if organizations work at the institutional level to ensure that internal policies and practices enable people-centered approaches. Organizations should take stock of their strategic planning documents, technical tools, cultural norms, and institutional will in order to identify good practices that should be reinforced, and areas that require further adaptation. This may require dedicated training and mentorship to fully integrate PCA principles and processes. Management support for the approach is also an essential ingredient for resisting the inclination for rapid response, and instead encouraging teams to take the time and space to engage with the affected community and collaborate with other actors in a multi-disciplinary way. They may also consider engaging senior leadership and donors to ensure that existing project management and funding expectations and procedures enable the flexibility and extended timelines required for the PCA. The PCA is most successful when various organizations working in a target area can come together and agree to jointly implement the PCA and contribute the necessary resources.

At the basis of this approach is the notion that self-determination is an essential element of human dignity. The PCA recognizes that affected communities are experts of their own situation, capable first responders and agents of their own protection and change.

Marta Pawlak, Initiator of the People-Centered Approach

FOSTERING MEANINGFUL PARTICIPATION

Very often, as humanitarians, we may have the belief that “we do it already,” we already put communities at the center of our work. However, there is an important distinction between “consulting” and “engaging” with people. When we consult people, we often use questionnaires to ask them about their needs, offer them a menu of pre-designed activities, do our own analysis to design a humanitarian response, and recruit beneficiaries based on their perceived alignment with the selected interventions. This supply-driven approach is often much more efficient in emergency contexts. However, it often misses critical opportunities to build on existing capacities and consider people’s self-determination.

Genuinely engaging with people means handing over the reins and recognizing that affected communities have the power to co-design humanitarian responses, and where possible, co-implement them. It recognizes people’s voice in identifying their main concerns, determining their own needs, and designing their own solutions. It acknowledges the diversity of people forming a community, and the fact that they have different needs and capacities. As a result, the PCA Roadmap systematically enables the active participation of communities throughout every stage of the process, from analysis to design and evaluation. Depending on the type of intervention, as well as community capacities, resources, and will, they may also be involved in implementation. This approach requires more time during the planning phase of the PCA Roadmap, but ultimately has the potential to produce more effective and durable protection outcomes.

Case Example: During a workshop, a group of women shared their concerns about the risk of being sexually assaulted by local armed actors when they go out to collect firewood. Some women reported that they stopped collecting firewood and started buying it at the local market instead. Others did not have the means to buy it in the market, or saw it as a lucrative source of income to continue collecting firewood and selling it at the market. The women who continued collecting firewood explained how they are trying to reduce the risks that they face: “One day before going to the bush, we requested to meet the commander of the armed group that is attacking us. We ask them to protect us. We know they are the ones harming us, but we want to raise in them the feeling of responsibility and turn them to our protectors.”

The women asked if the humanitarian organization could help them in their negotiation efforts by improving their skills or accompanying them. The humanitarian organization explained that this is not a service that they can offer; however, they could conduct an assessment and raise the issue in a confidential dialogue with the armed group. One of the women retorted, “Why would you speak about us without us? And most of your members, you are going to leave this place and we will remain here. We already have a dialogue with them. Why can’t you come with us and help us to get our message stronger?”

Sometimes in the PCA process, communities may propose solutions that are beyond the scope of activities that organizations typically implement. Embedding meaningful participation calls for organizations to creatively explore new approaches and demands full transparency along the way. In the case example above, the organization heard the women’s demands and eventually developed a program for humanitarian mediation to include affected communities in protection dialogue with diverse actors who influence their safety. Alternatively, the community may suggest solutions that are not in line with international norms or that can be harmful to a specific segment of the community (e.g., child labor as a coping mechanism for low household income), that do not comply with humanitarian principles (e.g., building trenches as to enable self-protection), for which sufficient quality cannot be ensured (e.g., providing dressing kits without medical staff), or for which humanitarian actors do not want to be held accountable (e.g., helping widows find husbands to reduce their vulnerability). In the PCA process, these types of limitations, constraints and do no harm concerns are consistently discussed directly with the community members in order to take informed decisions and uphold accountability to communities.

STARTING WITH A BLANK SLATE

The PCA requires organizations to enter communities with humility and a blank slate, not with a menu of pre-determined activities. During the initial analysis workshop, the first question is often: “What worries you?” This broad scope creates space for community members to identify the issues that are important to them, in their own words, and to start the conversations from what they assess as important. These open discussions encourage individuals to clearly voice their concerns, perspectives, and knowledge of the context. They can also be paired with participatory analysis tools, such as pair-wise ranking, problem trees, and the protection onion. Concretely, the PCA provides a platform where communities can share their analysis of threats and coping strategies and suggest potential solutions without resorting to questionnaires at the initial stage.

Case Example: During a PCA workshop, a group of farmers identified a lack of food as their main concern. The humanitarian organization facilitating the workshop did not initially recognize this issue as a relevant protection concern. After probing further, they learned that the farmers could not access their agricultural fields, because they were close to disputed areas, and the farmers risked being caught in the crossfire. The farmers had opted to stop tending their fields, but suffered from a loss of livelihoods and food shortages as a result. In consultation with the farmers, the humanitarian organization decided to provide special value crops that require less water, so that the farmers did not have to spend as much time in their fields. They also accompanied the farmers to negotiate with the local armed actors to ensure their safe passage on specific days, so that the farmers could resuming tending to their fields.

While the PCA uses a protection lens to approach communities’ priorities and concerns, it also recognizes the correlation between safety and protection on the one hand, and basic needs and services, on the other. Using a threats-based analysis as the entry point, rather than a need-based approach, helps to create space for communities to speak more broadly about the risks that they are experiencing. These are not always identified by communities or humanitarian organizations as protection risks; however, further discussion often demonstrates how protection concerns can be the causes and/or the consequences of the identified concerns. Moreover, the understanding of “protection” might be different for a community than it is for humanitarian actors. For most humanitarian actors, “protection” refers to notions of risk reduction, responsibilities of duty bearers, and respect of rights. For affected people, “protection” is frequently understood as physical safety, as well as access to resources and information that enable their safety or as connection to people who can influence their safety. What is most important is to develop a common understanding of the concerns causing harm to the affected community, of the available resources, and of potential solutions that can be addressed at different levels, by different actors, alongside the community.

During trainings, I ask the participants to stop thinking about checking boxes. Let’s deconstruct what you have learned! Come with a blank slate. For many, it’s intimidating to accept that you’re going to go and sit with the community and allow them to tell you the risks they care about. The only real skillset needed is to be curious; let yourself be guided by the community.

Marta Pawlak, Initiator of the People-Centered Approach

In many cases, the PCA is likely to generate suggested solutions that are beyond the typical portfolio of protection activities the organization was implementing. Wherever possible, organizations should aim to honor the “blank slate” approach by following through on the identified protection strategies. While not all options may be possible within the scope of humanitarian principles, internal mandates, resources, and technical expertise, committing to supporting communities in the ways that they believe will best achieve protection outcomes is essential to preserving their dignity and self-determination.

EMBRACING COMPLEMENTARITY

The PCA adopts a principle of complementarity in which diverse actors join efforts based on their comparative advantage to implement the most effective and efficient humanitarian response. This complementarity may occur between actors with different sectoral expertise, across the humanitarian development peacebuilding spectrum, and actors with different positionality across the local, regional, national, and international levels. A true spirit of complementarity strengthens partnerships, enables more coherent action for the benefit of affected people, and avoids the duplication of activities and assessment fatigue in communities.

Case Example: Community members identified child labor as a harmful coping strategy taken in response to poor household income. In collaboration with early recovery and protection actors, local social workers and a local women’s association organized a joint session with parliamentarians to advocate for an increase the number of people who could benefit from the state welfare system and to increase the amount of the allowance. The session had a positive impact, compelling the parliamentarians to review their criteria to access the welfare benefits. Meanwhile, the early recovery and protection actors supported illiterate female heads-of-household to apply for the allowance.

It is important for humanitarian organizations to recognize that before external support is deployed, local communities and existing structures often serve as the first responders. The PCA seeks to build on these capacities, rather than replacing or, at worst, undermining them. The PCA ensures that rather than co-opting local actors to transfer risk or to serve as force multipliers for their own activities, international organizations are engaging local actors in genuine partnership that sees them as equals in generating innovative and adaptive approaches. While the PCA often places international actors as the facilitators of the PCA process, in some cases, humanitarian organizations simply offer different resources, such as give local actors access to reputational capital and funding that they wouldn’t otherwise be able to tap into. Based on their respective capacities and positionality, local and international actors each implement the parts of the solution to which they can best contribute.

The PCA therefore encourages actors to go beyond information exchange and referral among agencies, to engage in joint assessment, analysis, and planning. This collaborative process can help identify collective outcomes as define by communities, as well as relative areas of expertise and available resources for response, so that implementation can also harness opportunities for synergy. As a result, the team or organization best positioned implements that part of the solution. Moreover, when humanitarian, development, and peacebuilding actors collaborate, responses are often able to not only address immediate protection concerns, but also set the foundation for addressing the drivers of conflict. Joint monitoring and evaluation can also enable collective learning and adaptation.

CLICK HERE TO EXPLORE OTHER CASE EXAMPLES OF RBP IN ACTION

CLICK HERESign-up

"*" indicates required fields