Introduction

1. Why a GBV Prevention Evaluation Framework?

In 2019, with the support of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), InterAction launched a two-year project to develop a Gender-Based Violence Prevention Evaluation Framework (GBV PEF), to help organizations measure and evaluate the outcomes of their GBV prevention work in humanitarian contexts.

This ambition is in line with the wider moves towards both outcome-oriented thinking and language among protection actors, and an increased concern for prevention activities within the GBV community. The IASC (2016) Policy on Protection in Humanitarian Action, for example, clearly defines protection outcomes as reduced risk for affected persons, in addition to providing a breakdown of what reduced risk can mean in practice:

DEFINITONS

- PROTECTION OUTCOMES:

A response or activity is considered to have a protection outcome when the risk to affected persons is reduced. The reduction of risks, meanwhile, occurs when threats and vulnerability are minimized and, at the same time, the capacity of affected persons is enhanced. Protection outcomes are the result of changes in behavior, attitudes, policies, knowledge, and practices on the part of relevant stakeholders.

IASC (2016) Policy on Protection in Humanitarian Action, p.15.

At the same time, humanitarian organizations working on gender-based violence in crisis settings are increasingly focusing on prevention activities alongside response. Yet their remains a lack of investment in understanding how to better design for, measure, and assess the outcome-level results of GBV prevention work.

In this light, InterAction undertook a scoping exercise in 2019, with a view to mapping the range of GBV risk patterns currently being addressed in crisis settings, the interventions undertaken, and the methods and tools used to track and measure prevention outcomes.[1]The study revealed the need for guidance on how to design and measure GBV prevention outcomes in terms of reduced risk of harm within the community, beyond the measurement of outputs, activities, and perceptions of services provided.

The study showed that, for many GBV prevention projects and programs in humanitarian settings, the analysis of GBV risks remains weak. Risk analyses were often generalized, aiming to tackle GBV as a broad form of violence, without paying attention to the specific patterns of GBV risk that exist and evolve in the crisis context in question. As a result, many of the prevention programs reviewed struggled to match the nuances of what was occurring in-situ, whether it related to intimate partner violence, sexual violence, early and forced marriage, trafficking, or other forms of GBV, and the source of the risk. This had implications for the project theories of change, which were generally not context-specific, reflecting a lack of confidence about which pathways could be taken to reduce and prevent specific GBV risks in the community context in question. Consequently, many projects focused on quite generalized risks with little consideration of local context, or sometimes focused entirely on risk mitigation through safe programming at the expense of specific GBV prevention activities.

In addition to project design weaknesses, the study noted the depth of the evaluation challenge for many GBV prevention projects and programs—with many such programs simply not appearing to be evaluable at all. By making it impossible to even begin evaluating these activities, organizations are depriving the humanitarian sector as a whole of the types of evidence about what works in preventing gender-based violence, for whom, and in what contexts. Core evaluability problems noted in the scoping study included:

- Unclear program designs, which often lacked any form of theory of change underpinning the choice of activities or target groups.

- Unclear or under-developed articulation of the intended outcomes of the GBV prevention activities.

- Missing baseline data and/or lack of a monitoring plan to overcome data gaps.

- Absence of appropriate disaggregation of data according to the specific vulnerabilities to the specific GBV threats present in the context in question.

Many of the challenges of measuring GBV prevention are well-known. Some forms of prevention—though not all—target long-term social norms change at the level of communities, institutions, and societies as a whole. Measuring this type of change requires a level of both time and investment that most humanitarian teams cannot access within the short timeframes of most program cycles. Likewise, the ethics of collecting data on GBV incidence within a community present clear challenges to quality data collection, analysis, and management. Even once outcome-level data has been collected and analyzed, the number of external factors that influence GBV risk can make it hard to demonstrate the contribution of specific program activities to observed change in the community. And rigorous causal attribution remains even more difficult to prove without the ability to establish robust control groups for counter-factual analysis of prevention efforts.

Nevertheless, outcome-oriented project design and measurement tools can help overcome these challenges. The tools presented in this framework are specifically designed to help agencies analyze GBV risk in emergency contexts, design results-oriented programs to reduce the risks observed, and develop measurement frameworks and evaluation approaches to demonstrate the effects of their interventions in the communities they serve.

2. What we mean by Gender-Based Violence

This Prevention Evaluation Framework (hereafter, ‘PEF’) is designed to support program design and evaluations for the prevention of all forms of gender-based violence, including sexual violence perpetrated against women and girls, men and boys, and non-binary and non cis-gendered identities.

We recognize that many organizations emphasize different aspects of gender-based violence in their policies and practice, and some have unique and importantly distinct definitions of what it is and what

drives it. For this reason, we have taken a broad, inclusive definition of gender-based violence, so as to allow project teams from across the organizational spectrum to locate their own GBV work within this

broader umbrella, and relate each Module of the PEF to their work as a result.

Gender-based violence (GBV) is an umbrella term for “any harmful act that is perpetrated against a person’s will and that is based on socially ascribed (i.e., gender) differences between males and females. It includes acts that inflict physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering, threats of such acts, coercion and other deprivations of liberty. These acts can occur in public or in private.”[2] The term ‘GBV’ is most commonly used to underscore how systemic inequality between males and females, which exists in every society in the world, acts as a unifying and foundational characteristic of most forms of violence perpetrated against women and girls.

While GBV also includes sexual violence committed with the explicit purpose of reinforcing gender inequitable norms of masculinity and femininity, GBV and violence against women and girls (VAWG) are often used interchangeably. In fact, the development of this definition was preceded by important debate on how to accurately capture that the majority of acts of GBV disproportionally impact women and girls, and are deeply embedded in the systemic inequality between males and females, but denote that all sexes and gender identities can experience acts of GBV.

GBV is also used to describe violence perpetrated against women, girls, men, boys with diverse sexual orientations and gender identities as well as non-binary individuals because it is “driven by a desire to punish those seen as defying gender norms”. To be clear, the PEF is designed to include all potential survivors of GBV, with special attention to the intersecting identities of people. This would include, for example, LGBTQI+ persons, adolescent girls with disabilities, women of minority groups, such as the Afro-Caribbean or indigenous; amongst others.

INTERSECTIONALITY AND GBV

Intersectionality is a framework for understanding that people experience overlapping (i.e., intersecting) forms of oppression, discrimination and marginalization based on their co-existing identities (e.g., inequality based on gender and/or ethnicity).

Not all at-risk groups will be exposed to – or experience – GBV in the same way. Women and girls as a group experience gender inequality and discrimination, and are at risk of GBV. But each woman and girl has different characteristics or identity aspects that will shape how they experience discrimination, and contribute to their risk of GBV. These can include age, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, disability, religion, civil status, and displacement and immigration status. Adolescent girls living with HIV/AIDS or a displaced woman with a disability will experience intersecting forms of discrimination and GBV risk. Similarly, a transgender man of a minority group will experience risk differently.

An intersectional lens must be applied to every element of results-based approach to GBV prevention. Understanding the context-specific intersecting forms of structural oppression, discrimination and risks that different people experience is critical to designing GBV prevention programs with reduced risk as an outcome.

3. What we mean by prevention

This framework is designed for any organization seeking to reduce the risk of gender-based violence occurring within humanitarian settings. This includes all activities with GBV risk-reduction as an intended outcome.

Throughout this framework, we understand the intended outcome of GBV prevention work to be a reduction in the GBV risk faced by communities and individuals living through crisis. For example, consider a program working with men and boys to change attitudes towards intimate partner violence in a displacement camp setting. The intended outcome here might be a reduced risk of violence by men committed on women within the household. This is closely related to, but distinct from, the results of the GBV prevention work, which we understand as the changes in attitudes, behaviors, policies and practices that underly GBV risk. So the intended results might be a reduced acceptance among the men and boys of the legitimacy of violence against female partners; or a change in the ways men and boys understand their rights, entitlements and obligations to the women in their household.

DEFINITIONS

- GBV PREVENTION OUTCOME:

The reduction in GBV risk faced by vulnerable communities and individuals.

- GBV PREVENTION RESULTS:

The changes in beliefs, attitudes, polices, norms, and behaviors that underpin GBV risk.

4. The Results-Based Protection Framework

This framework has been built on the foundation of the Results-Based Protection framework developed by InterAction and endorsed by a broad set of humanitarian actors, including INGOs, ICRC, and international organizations. The Results-Based Protection framework is a problem-solving approach used to address complexity and the ever-changing environment that surrounds protection issues in humanitarian action. It’s an approach which aims for results in terms of reducing the protection risks that people face. It underscores the importance of starting from the perspective of those experiencing violence, coercion, and deliberate deprivation, and embraces aspects of systems-practice, design-thinking, and other comparable methods that emphasize iteration, adaptability, relationships, interconnectedness, and strategic collaboration to achieve protection outcomes.[3]

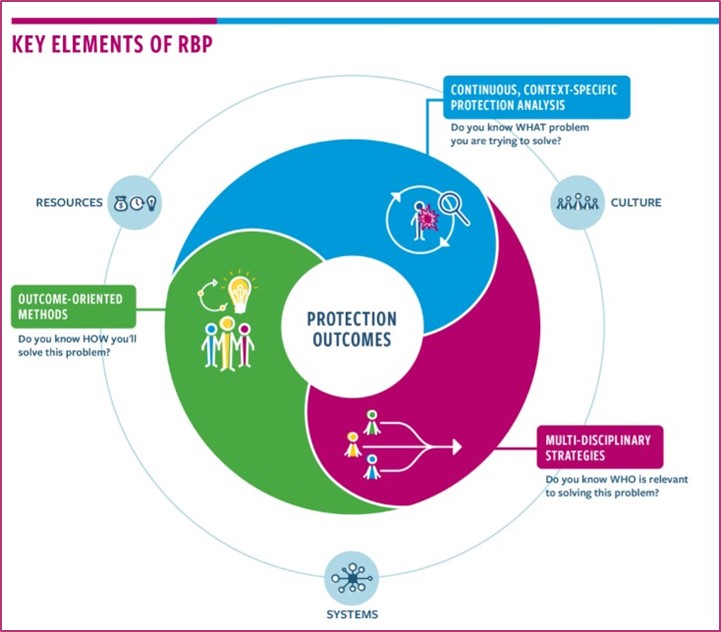

The framework includes three key elements, each of which are taken as essential to achieving protection outcomes:

- Continuous, context-specific protection analysis

- Multi-disciplinary strategies

- Outcome-oriented methods

The three elements are all intended to support a common goal of reducing protection risk, as illustrated in the following diagram:

Diagram 1. Results-Based Protection

These elements are comprised of various approaches, methods, tools, and practices that support protection results and outcomes:

- Continuous, context-specific protection analysis: risks patterns should be examined in their specific contexts, including their specific historic, political, socio-economic, and linguistic realities at the local, regional, and/or national level. This analysis should start from the perspective of affected communities, be comprehensive and updated regularly based on new information and changing dynamics.

- Multi-Disciplinary Strategies: most protection concerns require more than one actor for effective problem-solving. To achieve a protection outcome, each actor needs to be aware of their role and

responsibility toward meeting the outcome and design their intervention in relation to their specific strengths and contribution.[4] - Outcome-oriented methods: humanitarian action should be based on a clear causal logic with the goal of measurable reduction in risk. Methods that help navigate complexity are encouraged. Methods such as outcome mapping, systems-thinking, design thinking, and foresight analysis can be used to help define how to go about changing behavior, attitude, knowledge, policy, and practice for protection outcomes.

5. How this applies to GBV Prevention Work

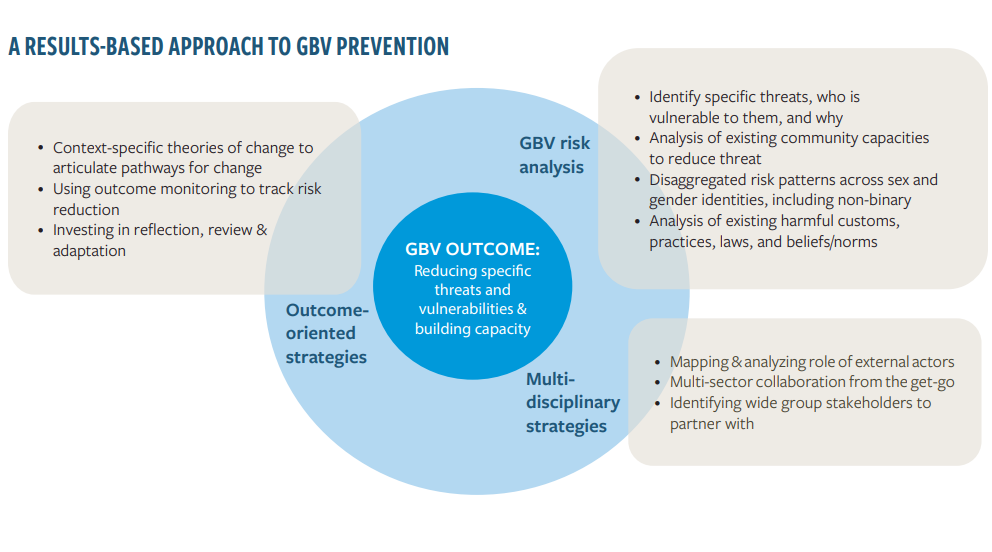

Each of the elements of the results-based protection framework have potential application to gender-based violence prevention programs, as illustrated below:

Diagram 2. Results-based GBV prevention

- Continuous, context-specific GBV analysis: GBV risk patterns should be identified and tracked on a context-specific basis. It is essential that such analysis starts from the perspective of the population, where it is safe to do so. This can help avoid the unconscious imposition of generalizations and assumptions about how GBV manifests itself in a community. Critical aspects to cover in the GBV analysis include: the specific nature of the threats present in the community being served, how these have changed over time, the different types of vulnerability community members have toward those threats, and the pre-existing capacities that community members already have to help reduce the risk of GBV arising from these threats. Given the potential for GBV to affect people of all gender identities, it is important to disaggregate risks faced according to gender and sexuality. It is also important to

map any pre-existing harmful traditional practices, beliefs and norms within the community being served, which may contribute to the GBV risk. This is especially important in order to counter-balance any preconceived ideas about how GBV manifests itself in the community in question. Moreover, in addition to ensuring this analysis work is done on a context-specific basis, it is also important to carry out a continuous analysis. The changing dynamics of humanitarian crises can affect the evolution of GBV risk, threat, vulnerability, and community-based capacity to mitigate threats. - Multi-Disciplinary Strategies: effective GBV prevention requires the cooperation of multiple actors. GBV prevention programs need to be designed on the basis of a clear mapping of external actors influencing GBV risk in the context in question. Multi-sector and multi-disciplinary collaboration should be encouraged from the first stage of the project cycle, including both within the different domains of the acting organization itself, and across the humanitarian space. This includes looking at actors both within and outside humanitarian action that might have a role to play to contribute to a GBV prevention outcomes, for example development actors, peacebuilding actors, academics, government, or diplomatic actors. Organizations should take time to identify a wide-group of relevant project partners, including different categories of local partner organization, from formal NGOs and local authorities to informal community groups and social networks.

- Outcome-oriented methods: results-based GBV prevention work should be based on a context specific theory of change with a clear pathway to change in terms of reduced GBV risk for community members. Outcome monitoring tools should be used to track risk reduction over time, in addition to observing the evolution in contributory factors such as social norms and attitudes toward GBV. In addition, and equally important, time and space for reflection and adaptation at project level needs to be created, so as to allow reflection on outcomes observed and adaptation of projects as GBV risks evolve.

Each of these points has guided the construction of this PEF, and each area explored in further detail in the modules below.

Perhaps the most important implication of applying this framework in this way, is the identification of GBV risk reduction as the primary intended outcome of GBV prevention work. This is in line with the move toward taking a results-based approach toward protection and GBV prevention activities. But it does have the potential to create confusion of terminology in the GBV community, where “risk mitigation” is commonly used to describe the efforts of sectoral humanitarian programs to reduce the risk of GBV associated with the provision and use of their own products and services in crisis contexts. To be clear, the definitions used in this framework do not speak to the difference between “primary prevention” activities and wider “risk mitigation” work. Instead, the framework speaks to the intended outcome of GBV prevention which is understood to be the reduction in GBV risk faced by vulnerable people and communities in crisis.

0.6 WHO IS IT FOR?

The framework has been designed to support dynamic and strategic program management that can help improve the measurement and evaluation of GBV prevention outcomes. It is intended to help humanitarians make strategic decisions about their prevention efforts. It is hoped that, by using different parts of the framework in an iterative manner to inform the various stages of the program cycle, program teams will be able to learn, adapt, and improve decision-making at project and program level.

Importantly, no specific level of technical expertise, resourcing, funding arrangements, or program context is assumed as a prerequisite for using this framework. Instead, we encourage program and evaluation teams to use this framework in the context of their current needs, constraints, and opportunities. Even, and perhaps especially, where these constraints are most extreme. Please start from where you are, not where you think you need to be.

For these reasons, the framework has been written for a wide-range of readers. This includes GBV country advisors, program managers, and officers. But it also includes program teams working on other, related areas of humanitarian response, when seeking to design for outcomes that include GBV risk reduction. This is relevant given the important role of multiple actors and disciplines when seeking to reduce GBV risk, as noted by Vigaud-Walsh (2020). As such, the language and approach of the PEF has been designed to be accessible to non-GBV specialists. Care has also been taken to make the language around monitoring and evaluation tools clear and accessible to program teams and non-specialists.

Moreover, the PEF is designed to be accessible to monitoring and evaluation teams (hereafter ‘M&E’ staff). This is important because of the need for close cooperation between program and M&E teams throughout the project cycle if outcome-level results are to be appropriately measured and interpreted. Involving M&E teams from the start of strategy development and program cycles can help ensure that outcome-level measurement informs the design process. The PEF itself was designed following a series of online workshops that brought together country-based program and M&E teams. These workshops highlighted the importance of engaging both sides of this divide when approaching M&E for GBV prevention work. In particular, the ethical constraints around GBV data collection mean that much of the primary data collection work needs to be conducted by program, rather than M&E, teams. As a result, it becomes even more important for program teams to engage closely with their M&E colleagues when designing measurement tools and systems, to ensure they yield high quality results-oriented data to inform future programming.

Lastly, it should be noted that the PEF focuses on the needs and constraints of country-level program teams, rather than headquarters staff or wider advocacy initiatives. This is due to the need for M&E guidance at project and program level, as demonstrated by Vigaud-Walsh (2020). The authors hope that headquarters staff and advocacy actors will find the PEF useful as a sign-post of what is possible when it comes to results-oriented GBV prevention programming. But the primary intended audience of the PEF remains country-level staff working in humanitarian contexts on projects and programs that seek to reduce GBV risk for crisis-affected communities.

0.7 HOW TO USE THE FRAMEWORK

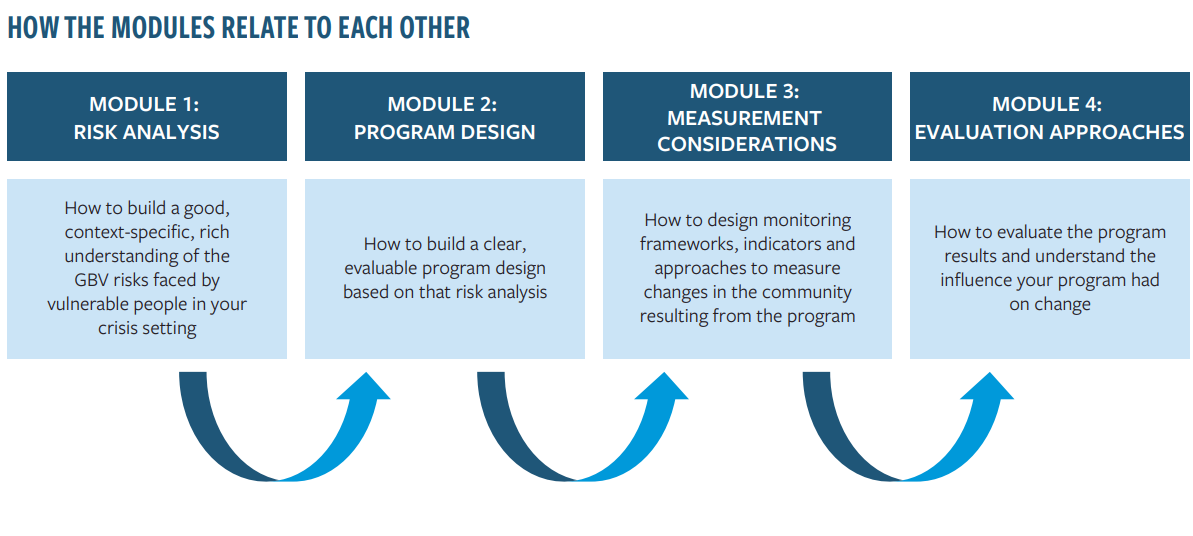

The GBV Prevention Evaluation Framework contains four modules, answering four main questions:

- Module 1 – Risk Analysis: How can program teams analyze the GBV risks faced by crisis-affected communities in a detailed and context-specific manner to better measure GBV prevention outcomes?

- Module 2 – Project Design: What should be done during the project design stage to enhance the evaluability of GBV prevention outcomes?

- Module 3 – Measurement Considerations: What should project teams and M&E staff consider when designing the monitoring system for projects working towards GBV prevention outcomes?

- Module 4 – Evaluation Approaches: What types of evaluation approaches are best suited to assess GBV prevention results and outcomes in conflict and crisis contexts?

The framework is designed for modularity, so each section can be read on its own, without covering the material in the other sections. That said, the relationship between strong project design and good monitoring and evaluation cannot be over-stated. For example, a well-constructed theory of change (covered in Module 2) will support a well-designed set of monitoring indicators (covered in Module 3). As such, there is some benefit to reading the framework in its entirety.

Lastly, the tools and approaches outlined in this framework have been selected with a view to fitting into the current constraints and practices of humanitarian organizations operating in crisis settings today. As such, the framework is not intended for use as a “stand-alone” product in addition to, and isolation from, all the risk analysis, project design, and measurement and evaluation work currently being done by teams on the ground. Instead, the tools and approaches included in this framework have been chosen because they have the potential to fit into current practice, with minimal additional time or resource investment. In many cases, such as the risk analysis tools, they have been structured around the question of how organizations can make the most of their ongoing data collection and community consultation practices—as well as drawing out and structuring program teams’ tacit knowledge of the contexts in which they work.