Integrating local response and spontaneous community-led protection strategies in crisis situations is a difficult endeavor. There has been an uptake in learning that highlights the significance of autonomous, community-led protection strategies among affected populations. Nevertheless, despite the increased attention, there has been moderate change in how the affected population is undertaking community-led protection strategies, how they are acknowledged, supported, and strengthened. One reason for this is the lack of practical methodologies to allow agencies to support community-led responses to humanitarian crises without adversely affecting expectations. Noting this, Local 2 Global Protection (L2GP) has concentrated on supporting practitioners to develop a systematic means of supporting crisis-affected population to lead their own responses to humanitarian disasters. It’s done so through a new approach referred to as Survivor and Community Led Crisis Response (SCLR). To document the learning from its efforts, L2GP has published a paper that explains existing knowledge and experience from its efforts related to SCLR.

Before we look at the learning and implications, what is SCL

SCLR is an approach that supports individuals and communities responding to humanitarian and protection crises. The approach uses microgrants to transfer power ad resources to existing groups allowing for provision of assistance and ability to scale up interventions quickly. The approach stems from research into how communities respond to crisis, recognizing that they are always the first and last responders in any context. SCLR is intended to be facilitated primarily by local teams of national NGOs (or relevant national government departments) and supported by international agencies as required. By ensuring that it is people-led, SCLR builds on the knowledge of the affected population and identifies opportunities for community-led protection strategies oblivious to outsiders.

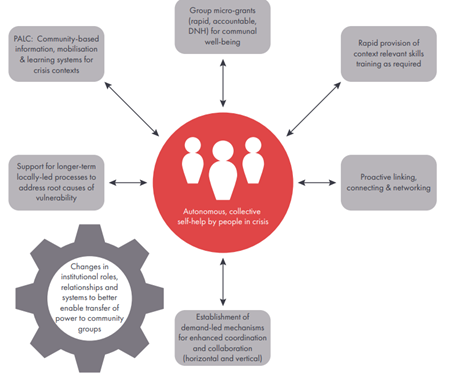

CORE COMPONENTS

SCLR consists of six components.

The first is referred to as Participatory action learning in crises (PALC). This involves community mobilization and facilitation that is interwoven with appreciative inquiry, identifying locally relevant do-no harm mechanisms, and supporting experiential learning and information sharing. The next component of SCLR consists of Group microgrants which involves a system of rapid, accountable and do-no-harm small cash grants as a means to enable and scale up collective action by citizens aimed at enhancing survival, protection, well-being, recovery, or transformation. Skills training that will help community-led groups increase the impact of their initiatives alongside actively linking, connecting, and networking the groups within the crisis to other organizations and programs that can support resilience are additional components of SCLR. The last two components of SCLR include Coordination and Resilience. Coordination includes supporting the development of locally relevant mechanisms for improving information sharing while Resilience entails proactively seeking opportunities for local groups to initiate and sustain their own longer-term transformative processes for tackling root causes of vulnerability. All the aforementioned components contribute to changes in organizational cultures and institutional relationships to allow SCLR to become good standard good practice in humanitarian programming.

Does it work? What’s the body of evidence?

hTough relatively new, there is a substantive body of work that indicates that SCLR is effective. With its partners, L2GP has published a paper titled ‘Survivor and Community-led response: Practical Experience and Learning by Justin Corbett, Nils Carstensen and Simone DI Vicenz.

Let’s start by taking at how SCLR has been implemented in Sudan

In 2011, as war began in Nuba, Sudan, the majority of international aid actors rapidly evacuated areas controlled by the armed opposition group. In the process, they left a war-affected population of more than a million people. Responding to the precarious situation, local NGOs in the region supported by some external actors, supported village-based protection and self-help groups. Volunteers began moving between villages undertaking training and awareness for residents and newly displaced people on basic, locally sourced survival and protection experience. These trainings included how families could better protect themselves during aerial bombardment, basic first aid, traditional medicine, psychosocial support and much more. By 2014, these activities had reached an estimated 400,000 people.

The number of casualties has greatly lessened, and people are somehow able to cope better with both the bombings and the fear of the bombings”

Nagwa Musa Konda, then director of NRRDO

By 2016, the conflict in Nuba had become less intense and aerial strikes eventually stopped altogether. With the situation changing, local protection groups shifted their priorities and opted to spend small group cash grants, sponsored through and SCLR initiative on collective farming of cash crops, which in turn supported basic education for children and adult literacy classes. The flexibility to change focus and address different needs, threats and opportunities did not require an external driven needs assessment. Rather, it happened by building on community-based solutions and coping mechanisms which already existed.

Another example of SCLR in practice is in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (oPt) where it has supported protection responses to gender-based violence and supported psychosocial support sessions, all issues of collective concern. A female protection group member in the village of Raboud on the Palestinian West Bank highlighted the empowerment approach of SCLR by noting that

The project succeeded because we worked together in the village. Many other NGO projects have failed – mostly because we were not really involved in the ideas and the plans. We did the electricity project cheaper, faster, and better ourselves than any NGO could have done. But most important of all – we feel it is our own project – our own work

Although there are promising signs of SCLR, there is still room for additional learning. What if agencies do not have a level of community facilitation skills? In less mainstream contexts, will SCLR still be as effective? These questions will need to be answered to ensure that SCLR is successful across all contexts.

Nevertheless, the evidence presented above suggests that SCLR as an emerging practice allows humanitarian and protection actors to provide effective support for locally led action during sudden or protracted crises. SCLR can be applied rapidly, at low cost and at scale by national and local NGOs as a complement to the needs-based approach of mainstream humanitarian.